The Crash of the M2-F2… Bruce Peterson and "The Six Million Dollar Man" Edwards AFB, CA May 10th, 1967  The idea of lifting bodies originated around 1957 by Dr. Alfred J. Eggers Jr. of Ames Aeronautical Laboratory. Scientists had been investigating the problems associated with reentry of missile nose cones and discovered that a blunt nose cone was a better than a pointy nose shape to endure the aerodynamic heating related with the friction of reentry from space. Eggers found that, with a slight modification, the symmetrical nose cone shape could be used to produce aerodynamic lift, and enable the modified shape to fly back from space rather than plunge to earth in a ballistic trajectory. The idea of lifting bodies originated around 1957 by Dr. Alfred J. Eggers Jr. of Ames Aeronautical Laboratory. Scientists had been investigating the problems associated with reentry of missile nose cones and discovered that a blunt nose cone was a better than a pointy nose shape to endure the aerodynamic heating related with the friction of reentry from space. Eggers found that, with a slight modification, the symmetrical nose cone shape could be used to produce aerodynamic lift, and enable the modified shape to fly back from space rather than plunge to earth in a ballistic trajectory.

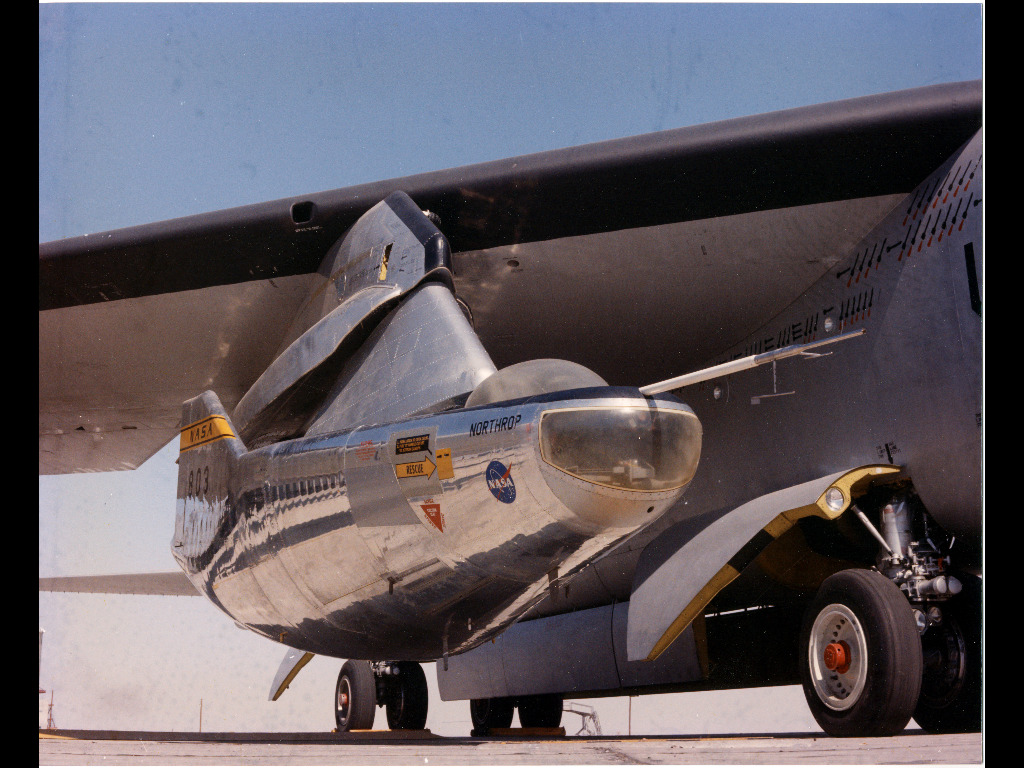

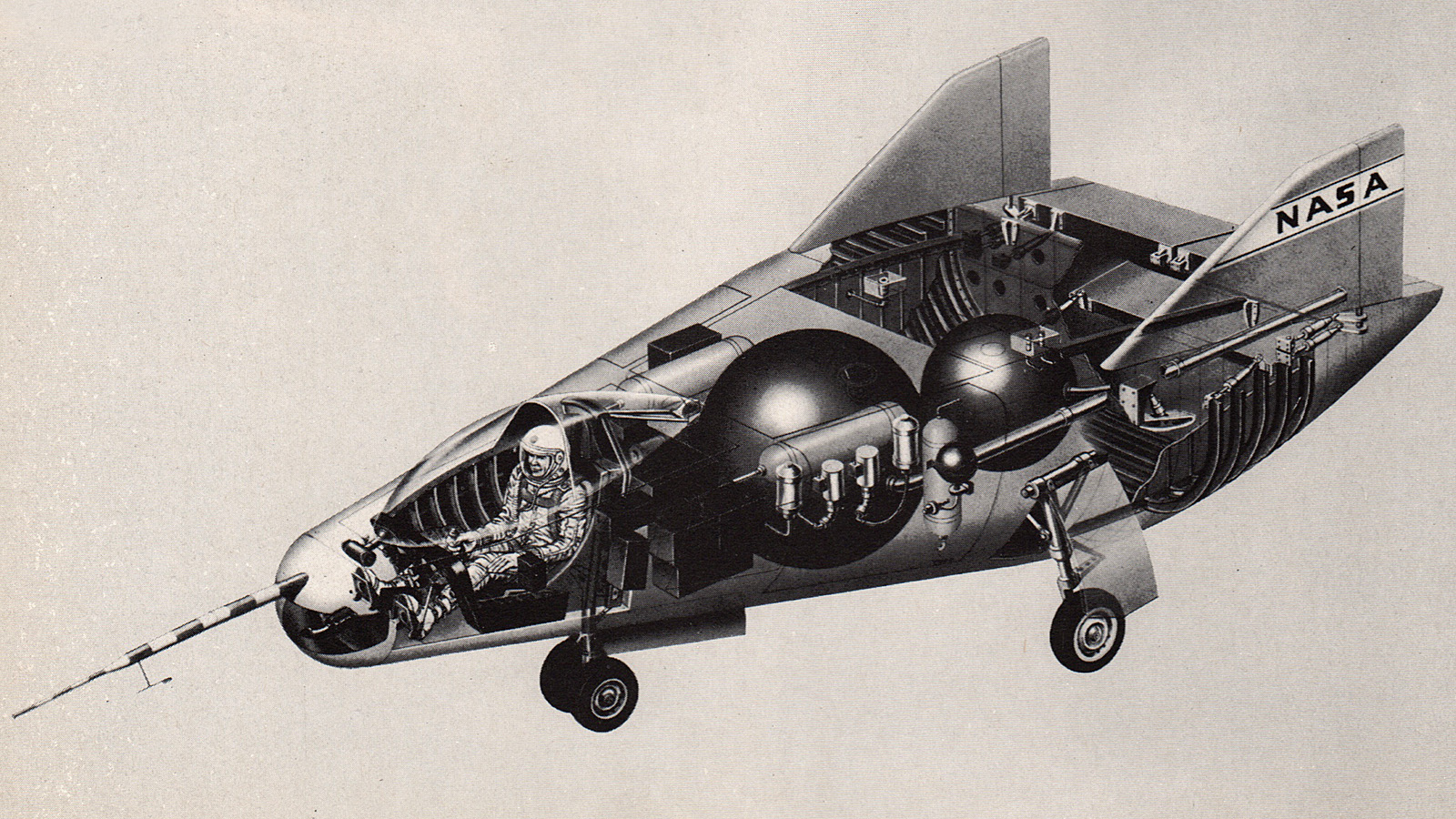

A fleet of lifting bodies was built for and flown at the NASA Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California. From 1963 to 1975, they would demonstrate the ability of pilots to maneuver, using stabilizing fins and control surfaces, the wingless vehicle to fly back to Earth from space and would land like an aircraft safely at a pre-determined site. The data the lifting body program generated contributed to the later development of the Space Shuttle program.  The first lifting body constructed and flown, the M2-F1, was a success, and it led to NASA's development and construction of two follow-on designs - heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers. The M2-F2 and the HL-10 were both built by the Northrop Corporation, and their names stemmed for their manufacture: the "M" referred to "manned" and "F" referred to "flight" version, and the "HL" came from "horizontal landing" and the 10 for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by NASA’s Langley field center.  The first flight of the Northrop M2-F2 - which looked very similar to the original "F1" - was on July 12, 1966. Weighing 4,620 pounds, the M2-F2 was 22 feet long and had a width of about 10 feet. With Milt Thompson as the pilot, was dropped from the wing pylon mount of a Boeing B-52 bomber at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The same B-52 – “Balls Eight” – was used to air launch the X-15 rocket research aircraft, and had also been modified to carry lifting bodies. The first flight of the Northrop M2-F2 - which looked very similar to the original "F1" - was on July 12, 1966. Weighing 4,620 pounds, the M2-F2 was 22 feet long and had a width of about 10 feet. With Milt Thompson as the pilot, was dropped from the wing pylon mount of a Boeing B-52 bomber at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The same B-52 – “Balls Eight” – was used to air launch the X-15 rocket research aircraft, and had also been modified to carry lifting bodies.

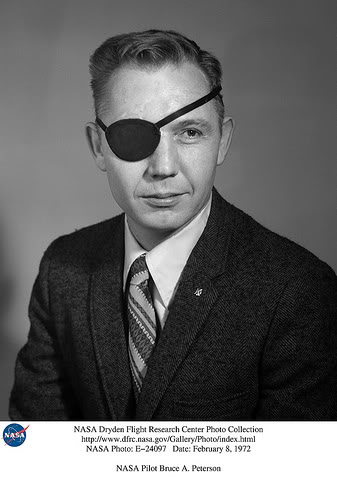

After Milt Thompson had retired from flying in late 1966, Bruce Peterson became the NASA project pilot for the lifting body program. A NASA Dryden research pilot, Peterson had previously flown the M2-F1 and had made the first glide flight of the HL-10 in December 1966. Bruce Peterson...  A native of Washburn, North Dakota, Peterson was born on May 23, 1933, to Pauline and Albert Irving Peterson. His family moved to Banning, California, and he attended the University of California at Los Angeles and the California State Polytechnic College at San Luis Obispo. Following his UCLA stint, Peterson enlisted in March of 1953 in the Navy as an aviation cadet and was later commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps in 1954, where he became a pilot. Peterson received his Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from CalPoly in 1960 and then joined NASA after graduation as an aeronautical engineer. A native of Washburn, North Dakota, Peterson was born on May 23, 1933, to Pauline and Albert Irving Peterson. His family moved to Banning, California, and he attended the University of California at Los Angeles and the California State Polytechnic College at San Luis Obispo. Following his UCLA stint, Peterson enlisted in March of 1953 in the Navy as an aviation cadet and was later commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps in 1954, where he became a pilot. Peterson received his Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from CalPoly in 1960 and then joined NASA after graduation as an aeronautical engineer.

After graduating from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School in 1962 as a member of Class 62C at Edwards Air Force Base, California – the first NASA pilot to do so - he transferred to flight operations at the Flight Research Center. There, he became a project pilot on the Rogallo paraglider research vehicle (Parasev) program, which evaluated the use of a flexible – and inflatable – wing to safely return manned space vehicles. Peterson made his first research flight in the Parasev on March 14, 1962, but was injured when the aircraft unexpectedly dropped from an altitude of 10 feet during a ground tow flight. After the crash, his first question was, "What happened to the lateral stick forces?"  On December 3, 1963, Peterson first flew the M2-F1 Lifting Body. Nicknamed the "flying bathtub," the M2-F1 was a lightweight, unpowered prototype aircraft, developed to flight test the wingless lifting body concept. He flew the M2-F1 forty-two times in glide flight and made the first flight of the HL-10 on December 22, 1966. On December 3, 1963, Peterson first flew the M2-F1 Lifting Body. Nicknamed the "flying bathtub," the M2-F1 was a lightweight, unpowered prototype aircraft, developed to flight test the wingless lifting body concept. He flew the M2-F1 forty-two times in glide flight and made the first flight of the HL-10 on December 22, 1966.

During that short, three minute flight, a problem involving airflow across control surfaces made it almost unflyable, but Peterson still managed to land it safely. As a result of the data collected during the near disastrous flight, the HL-10 was adapted to prevent similar problems, going on to become one of the most successful lifting body concepts. May 10th, 1967  Peterson made his fourth glide flight, piloting the M2-F2 on May 10, 1967– the 16th overall flight of the program, and was scheduled to be the last one before the powered flights began. Peterson launched away from “Balls Eight” at 44,500 feet, heading to the north and flying east of Rogers Dry Lake. All went well as the M2-F2 sank like a stone at a speed of 400 miles per hour until the wingless craft reached 7,000 feet. Then, flying with a “very low” angle of attack, the lifting body began a “dutch roll” motion - a form of pilot-induced oscillation (PIO) - rocking from side-to-side at over 200 feet per second. Peterson, who earlier had turned that nearly uncontrollable flight in the HL-10 into a brilliantly successful landing, was an excellent pilot; he quickly and instinctively raised the nose, damping out the lateral motions. The recovery from the PIO had carried the craft away from its intended flight path. The pilot realized he was too low to reach the planned lakebed landing site near Runway 18 and was rapidly sinking toward a section of lakebed that lacked visual runway reference markings, which were needed to estimate height above the lake with accuracy.  At this point, a rescue helicopter appeared in front of the M2-F2. Peterson, overburdened, disoriented from the rolling motions, now had an additional worry. He called, “Get that chopper out of the way,” At this point, a rescue helicopter appeared in front of the M2-F2. Peterson, overburdened, disoriented from the rolling motions, now had an additional worry. He called, “Get that chopper out of the way,”

"Okay, Bruce, get ready to shoot your landing gear," replied control. Seconds later, Peterson retorted: “Roger - that chopper’s going to get me, I’m afraid.” Chase pilot John Manke, flying an F5D, assured Peterson the helicopter was clear, and it did chug off, out of Peterson’s path. Realizing he was very low, Peterson fired the landing rockets – a four-chamber XLR-11 rocket engine - to provide additional lift and the M2-F2 flared nicely. “He's all right," said a ground control officer."Okay, you're clear. Watch your gear, Bruce.” He lowered the landing gear, which needed only one-and-a-half seconds to deploy from up-and-locked to down-and-locked. But time had run out. Nearly 4 minutes after release from the drops ship, and before the gear locked, the M2-F2 hit the lake, shearing off its telemetry antennas. "Okay, he landed; without his gear," a second ground officer said. The craft began to somersault. "Get the fire truck out," said the second officer. "Come on, get the fire truck out there immediately." In the control room, engineers like Dale Reed saw the needles on their instrumentation meters flick to their null points. Startled, they looked up to the video monitor - in time to see the M2-F2, as if in a horrible nightmare, rolling over and over across the lakebed at nearly 250 miles per hour. It bounced, tumbled and rolled over six times before coming to rest – upside down - on its flat back, its canopy crushed, main gear seared, and right vertical fin destroyed.  Pulled from the wreckage by Jay L. King and Joseph D. Huxman, Peterson was rushed to the Edwards hospital for emergency surgery, then to the hospital at March Air Force Base, and several days later to UCLA’s University Hospital. Hospital. He suffered a fractured skull, broken teeth, and broken bones in one of his hands, plus had his a portion of his forehead scraped off. Pulled from the wreckage by Jay L. King and Joseph D. Huxman, Peterson was rushed to the Edwards hospital for emergency surgery, then to the hospital at March Air Force Base, and several days later to UCLA’s University Hospital. Hospital. He suffered a fractured skull, broken teeth, and broken bones in one of his hands, plus had his a portion of his forehead scraped off.

Lessons - “We can rebuild… We have the technology.” Instead of dumping the M2-F2’s remains to a scrap yard, NASA returned them to Northrop’s Hawthorne plant. Technicians placed the battered lifting body in a jig to check alignment, removing the outer skin and portions of the secondary structure.  The inspection took 60 days. In March 1968 NASA’s Office of Advanced Research and Technology authorized Northrop to restore the primary structure and return the vehicle to FRC. There it remained while lifting body advocates from Ames and Dryden determined its future. In light of its poor handling characteristics, the craft obviously needed modification. By this time the rival HL- 10 was already demonstrating superior handling qualities. Nevertheless, the M2 shape still appeared worth studying; on 28 January 1969 NASA Headquarters announced that the agency would repair, modify, and return the M2-F2 to service as the M2-F3. The inspection took 60 days. In March 1968 NASA’s Office of Advanced Research and Technology authorized Northrop to restore the primary structure and return the vehicle to FRC. There it remained while lifting body advocates from Ames and Dryden determined its future. In light of its poor handling characteristics, the craft obviously needed modification. By this time the rival HL- 10 was already demonstrating superior handling qualities. Nevertheless, the M2 shape still appeared worth studying; on 28 January 1969 NASA Headquarters announced that the agency would repair, modify, and return the M2-F2 to service as the M2-F3.

NASA pilots and researchers discovered that – despite having a stability augmentation control system - the M2-F2 had lateral control problems. The successor M2-F3 was modified with an additional third vertical fin - centered between the tip fins - to improve these handling characteristics.  Peterson, on the other hand, was permanently scarred by the crash. He recovered but lost vision in his right eye due to a secondary staph infection, then developed hepatitis and allergy to penicillin while undergoing skin grafts and reconstructive surgery to build a new eyebrow and eyelid. This accident was witnessed by futurist and aviation expert Martin Caidin, who was inspired to write a fictional novel – Cyborg - detailing the crash of test pilot, Steve Austin, and his subsequent implantation with ‘bionic’ technology. When the book became the basis for a 1973 TV movie, portions of film footage of Peterson’s final M2-F2 flight and crash, intercut with some scene of HL-10 operations, appeared. When the storyline continued, the footage reappeared in the opening credits of the follow-on series, “The Six Million Dollar Man,” despite Peterson’s dislike of having his accident replayed on television weekly. "About what is seen on the TV screens every week is what I remember," he stated in a 1975 interview. "That partial footage was taken by the cockpit cameras. I blacked out about the same time the cameras stopped working.” However, despite the injuries, Peterson continued at NASA Dryden. He worked as the Research Project Engineer on the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire program of the late 1960s and early 1970s and later assumed overall responsibility for Safety and Quality Assurance at Dryden. He continued to fly support missions, occasional research flights for NASA, and flying for the Marine Corps Reserve - serving as commanding officer of the Reserve Marine Aircraft Group-46 at the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station - until 1971. During his career, Peterson logged more than 6,000 flight hours in nearly 70 types of aircraft, and NASA awarded him with their Exceptional Leadership Award for his work on preparations for the first Space Shuttle landing in April 1981. After retirement from NASA, Peterson worked in Northrop's Advanced Systems Division – responsible for the B-2 “Spirit” stealth bomber - at Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, from 1982 until 1994 and later became the manager of system safety and human factors at Edwards AFB. Peterson became a fellow of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, and was a recipient of the Tony LeVier Flight Test Safety Award in 2002, and - in 2003 - he was inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor in Lancaster, California. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It hangs today in the Air and Space Museum’s Space Galley along with the first X-15, which was its hangar mate at Dryden from 1965 to 1969. Bruce Peterson passed away on May 1st, 2006, at 72 years of age in Laguna Niguel, California, and was laid to rest at Joshua Memorial Park in Lancaster. |