Skill versus Luck… Part 2 of the Hoover WW2 Trilogy Off the coast of Nice, France 9 February 1944 (Continued from Part 1)  Across the Atlantic Across the Atlantic

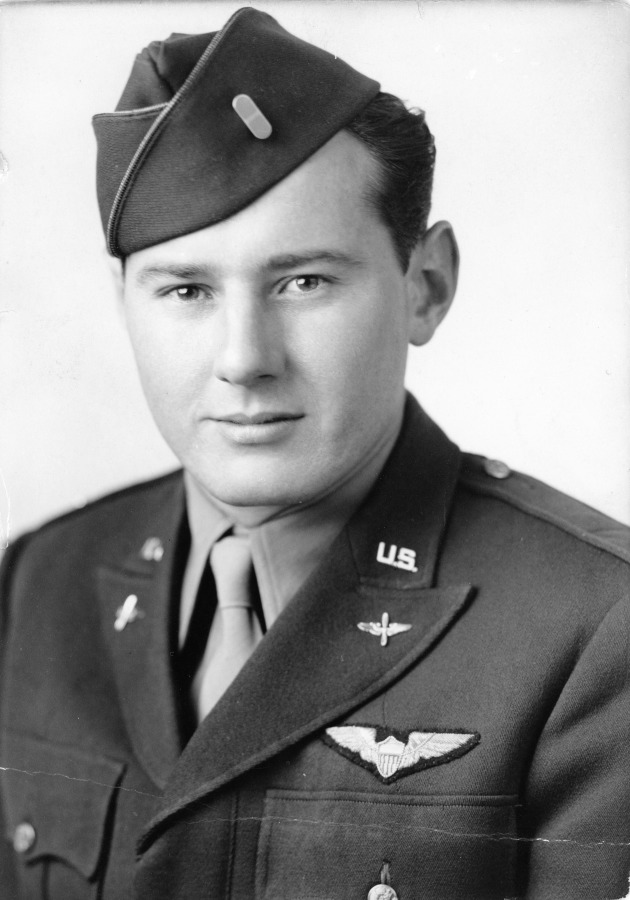

His skill as a pilot singled out Hoover and, despite only holding the rank of Sergeant, he was put in charge of 67 pilots as the unit cross the ocean aboard the RMS Queen Elizabeth. The group underwent additional training on aircraft recognition for aerial combat and ground evasion techniques for if forced to bail out over enemy-held territory. He was promoted to Flight Officer (the service’s equivalent to a non-commissioned Warrant Officer) with his fellow enlisted pilots shortly before Christmas 1942 After for combat, his unit was sent to Mediouna, Morocco, as part of a replacement pilots’ pool. Shortly after they arrived, Hoover was introduced to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning that a French major delivered. After the major conducted an aerial presentation of the plane’s abilities, Hoover followed by performing a low-level airshow that exceeded the expectations of all assembled. His commanding officer was furious, and yet impressed. Hoover was given a pro forma reprimand for the stunt, and the promise of the first combat assignment out of Morocco. But that would have to wait, as his skills were required in Oran, Algeria, to flight test newly-assembled P-39s, P-40s, Spitfires, and Hurricanes that were ready for service. Hoover used the opportunity to fly each plane to the full range of spins and aerobatics, entertaining the mechanics but annoying his new commanding officer, who temporarily grounded the pilot. Gaining Experience… Hoover returned to test flying, and endured numerous close calls with the aircraft he tested. He and his friend, Tom Watts, choose to conduct their test away from the field. One day, while the pair were flying P-40s over Africa’s Atlas Mountains, both experienced engine difficulties and broken radios. Suddenly, the engine of Watt’s plane stuttered and quit. The aviator was forced to land on the rocky desert floor as Hoover watched and circled overhead. Not wanting to leave his colleague in the wasteland, Hoover landed his plane nearby and picked up the downed pilot.  As the P-40 is only a single seat airplane, the pair took off their parachutes and Watts sat on Hoover's shoulders, hunched down low behind the rear-view mirror. Upon taking off, Hoover struggled to keep his plane’s engine working as they climbed to 8,000 feet to cross the mountain range. But some ten miles from their home base, Hoover’s engine quit as well, and the pilots were forced to glide. Fortunately, the P-40 has enough altitude to make their intended runway. As the P-40 is only a single seat airplane, the pair took off their parachutes and Watts sat on Hoover's shoulders, hunched down low behind the rear-view mirror. Upon taking off, Hoover struggled to keep his plane’s engine working as they climbed to 8,000 feet to cross the mountain range. But some ten miles from their home base, Hoover’s engine quit as well, and the pilots were forced to glide. Fortunately, the P-40 has enough altitude to make their intended runway.

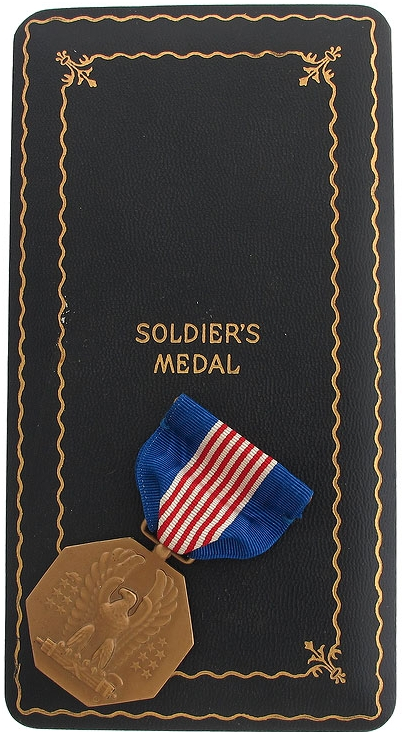

Afterwards, Watts’ report on the incident recognized Hoover’s role in the successful outcome, and the U.S. Army Air Forces awarded him the Soldier’s Medal. A recovery crew went out to Watt’s P-40 and repaired it, but the test pilot, who attempted to fly it back, was killed when it crashed on takeoff. While Hoover hated flight testing, as it kept him out of combat, it did provide him valuable experience and skills. But a series of meetings and promises resulted in Hoover’s assignment in September of 1943 to the 52nd Fighter Group, 4th Fighter Squadron, to fly P-38s shortly after the Allied invasion of the Italian island of Sicily. His initial duties involving escorting cargo vessels and no combat. But Hoover’s reputation as a master pilot was becoming known throughout the Army Air Forces, and a unique challenge arose that only his talents could rise to. A Tailor-Made Test… A Martin B-26 “Marauder”, a twin-engine medium bomber, had been attacked and forced to land on a short stretch of beach in the Straits of Messina. Repair crews had fixed the bomber, but no one thought there was enough room to fly the plane out. Hoover’s commanding officer presented the challenge to Hoover, who accepted. He and a mechanic went to look at the bomber, and discovered in was on a 1,000-foot crescent-shaped stretch of sand with a severe drop-off into the water at one end. Realizing he was going to need every iota of performance from the plane and its engines, Hoover studied the plane’s manuals and determined that every non-essential item would need to be removed from it.  Over the course of a month, the mechanic and a crew of 10 men removed the nearly all of the plane’s seating, most of the instruments and everything else that wasn’t absolutely needed to fly the plane. On the day of the flight, Hoover had less than 100 gallons of fuel and taxiing the bomber onto a 600-foot long section of steel matting that was connected to an extension of chicken wire. Over the course of a month, the mechanic and a crew of 10 men removed the nearly all of the plane’s seating, most of the instruments and everything else that wasn’t absolutely needed to fly the plane. On the day of the flight, Hoover had less than 100 gallons of fuel and taxiing the bomber onto a 600-foot long section of steel matting that was connected to an extension of chicken wire.

With reporters from the military newspaper, Stars & Stripes, on hand to witness the feat, Hoover recalled: “I ran up the R-2800 engines, dropped my quarter flaps, and off I went. The B-26 accelerated quickly, as light as it was with a minimum fuel load. Down the makeshift pierced steel planking, PSP, runway we went. I had a total of about 1,100 feet to play with. It was all or nothing. There was only four feet of clearance on each side, so I had to steer dead center to make it. Not only that, but what went for a runway was not only narrow but ran up an incline—no wonder no one thought I could make it out of there. I watched the airspeed as it climbed to twenty, then thirty, then fifty knots. At that point I had only about four hundred feet of pierced steel planking left in front of me. The end of the beach was quickly approaching and the nose still wasn’t up. Over those last four hundred feet I gained fifty more knots and the Marauder lifted its nose and pitched skyward as we came to the end of the PSP. Wow, what a beautiful day that was!” Hoover was able to take off successfully and get the plane to Palermo. For this feat of airmanship, Hoover was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Shortly thereafter, the 52nd Fighter Group relocated to Calvi on the French island of Corsica – and Hoover would finally see action!  Careful What You Wish For… Careful What You Wish For…

With 1,400 hours of flight experience, Hoover was on his 59th mission on the afternoon of February 9, 1944. Flying a Supermarine Spitfire Mk Vc, tail number MA883 and callsign “Black 3,” off the Italian and French coast covering an area from Cannes to Genoa, the objective of “Clatter Black” Flight was spotting and harassing and enemy ships. Each plane in the flight was equipped with small bombs to attack, and an externally mounted drop tank on its belly to extend their time in flight. “Black 1” was flown by Flight Officer James H Montgomery Jr, “Black 2” was 2nd Lieutenant Henry E Montgomery, and “Black 4” was 1st Lieutenant Bradley Smith. F/O Montgomery has been shot down before, a few months earlier over the Mediterranean Sea near Palmero by a German Messerschmitt, and spent a day afloat in a life raft before rescue, using his survival knife to spear a fish to eat. The story of his shoot-down and survival made national news in the United States, and he was dubbed the “Robinson Crusoe of the Skies” of American Spitfire pilots.  | | "Hoover’s Flying Spitfire" by Sam Lyons |

The first portion of the mission involved strafing a German cargo freighter amidst heavy anti-air flak at the port of Savona, Italy. Successfully damaging the vessel, the four Spitfires returned to base for refueling and rearming. Shortly before 2pm, the flight of four returned to their patrol, climbing to 10,000 feet. Thirty-five minutes into the patrol, they spotted a small German naval convoy off the coast of Nice. One by one, the Spitfire dove onto the ships, strafing the decks and dropping their bombs. After the last pass, made by Black 4, who made a direct hit on one. The climb to a safer altitude painted a barrage of 20-millimeter gunfire, and Hoover congratulated Lt Smith on the successful bombing and directed the formation to reform near Nice Harbor. But seconds later, someone radioed the flight “Four-ship formation inbound at 9 o’clock.” Enemy Encounter Four light blue & white-camouflaged Focke-Wulf 190 “Würger” fighters – lined up wingtip to wingtip at 5,000 feet - had sighted the Spitfires, and pounced upon their prey. Black 1 shouted over the radio, “They’re 190s – watch it!”  | | "Seconds Later My Engine Exploded" by Colin E. Bowley |

The four Fw190s broke their formation and – instantly – adrenaline started pumping through Hoover’s veins. This was a real dogfight, not practice! A pair of Fw-190s swung in behind Black 1, and Hoover radioed from him to “Break left” but it was too late. All hell had broken loosed, and in a firestorm of flak from below and tracers rounds from behind, and the Spitfire, with F/O Montgomery aboard, spun and burst in flames. Recognizing the need for maximum performance, Hoover pulled the tank release to get rid of external fuel tank – and the handle came off in his hand… With the maneuverability and speed of his Spitfire limited, the odds were stacked against Hoover – as the Fw190s, capable of speeds of 350 mile per hour, could outperform the Spitfire’s 215 mph. “It’s like racing a Model T Ford with a Cadillac,” Hoover recounted. With the Spitfire’s superior turning ability now his only defense, he headed straight for a German fighter. He headed for one of the German fighters and pulled the trigger, lighting up his .50 caliber cannons upon his foe. Working as a team, with faster airplanes, advanced Luftwaffe dog-fighting techniques, and more experience, the Fw 190s came after Hoover’s Spitfire and – try as they might – both of his wingmen, Black 2 & 4, when unable to help, having exhausted their aircraft’s ammunitions in the early minutes of the battle. It was four versus one. As his fuel-laden aircraft was slower than they anticipated, it caused the German fighters to overshoot – an unwitting advantage Hoover leveraged. But as he got one in his sights, his own airplane got lit up from below - sending shrapnel throughout his cockpit, and tearing the lower half of his body.  | | "One Heck of a Deflection Shot" by Heinz Krebs |

“Well they got old Hoover,” he radioed to his comrades. “I’ll try to stay a little longer – maybe I can get one of the bastards!” Hit! Breaking and juking the Fw 190s, Hoover fired off a last burst from his guns and just as his own engine exploded. With the nose of his airplane a roaring ball of flames, and oil covering the windshield, Hoover realized his Spitfire was finished. With a FW 190 still on his tail, Hoover made a final radio transmission, “They got me for sure this time.” He asked for a rescue plane, a British amphibious codenamed “Dumbo,” and started preparations for aerial egress from the stricken Spitfire. Without any power from the engine, he rolled the cockpit canopy open, rolled the plane inverted, and bailed out - high enough that both of his wingmen could see his parachute near the water. The section leader, Black 4, also saw something else: a pair of speed boats headed for the downed aviator... The remaining Spitfires, fatigued and without any remaining ammunition, racing back to their home airfield in Calvi. Ambush Aftermath… Squadron mates, led by Major William M. Houston, searched for Hoover and Montgomery, enduring an attack from another wave of German Fw 190s fighters. In that skirmish, Lt. John L. Bishop was shot down six miles southeast of Cannes, France. None of the downed airmen were located, but failed to locate either. All three Americans – Lt. Bishop, F/O Montgomery, and F/O Hoover – were shot down down by the same German pilot from Jagdgeschwader 2: Siegfried “Wumm” Lemke. Lemke would end the war with between 70 and 96 aerial victories, or “kills,” to his credit and receive the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross recognize his extreme battlefield bravery. To Part 3 of the Hoover WW2 Trilogy... Go back to Part 1 of the Hoover WW2 Trilogy... |