The Trans-Atlantic Flight of the 'America'June 29th - July 1st, 1927After his 1926 flight over the North Pole, then-Commander Richard E. Byrd, USN, was not happy with simply being the leader of the first flight over the North Pole. Byrd had planned the first trans-Atlantic flight completed by the U.S. Navy in 1919. So, in February of 1927, Floyd Bennett, long-time partner of Byrd and co-pilot of his famed North Pole flight, announced the intention to attempt to win the 'Orteig Prize', the $25,000 reward offered in 1919 by Raymond Orteig, owner of the Hotel Lafayette in New York City, for the first successful non-stop flight from New York City to Paris. Byrd was interested in the flight, albeit for simply scientific purposes. The Mighty AtlanticIn March of 1927, Byrd announced he had the backing of the 'American Trans-Oceanic Company, Inc.', which was established in 1914 by Rodman Wanamaker with the purpose of building the aircraft to complete the harrowing journey. Having gained the financial backing of Wanamaker's department store (where the airplane for Byrd's first historic flight was displayed), Byrd seemed, for a time, to be a serious contender, and heavy favorite, for winning the Orteig Prize, despite competitors from several other nations, including France, England, and Italy.

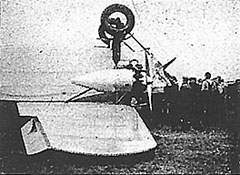

However, during a test flight of Byrd's airplane on April 16th, 1927, Byrd observed the tail of the aircraft as it sped down the runway. The plane went over its nose and crashed at Hasborough, New Jersey, injuring three of the four aboard, and slightly damaging the plane. Byrd fractured his wrist, but Bennett, who was pinned against an engine, suffered a broken leg and collarbone, dislocated shoulder, and serious head injuries, while George O. Noville, the plane's flight and fuel engineer, endured an operation to remove a blood clot.

Anthony Fokker, the airplane's designer, did not even suffer a scratch. With Bennett hospitalized for several weeks to come, Byrd was forced to find a replacement for him, delaying the anticipated flight. Byrd needed a solid navigator and instrument pilot as the replacement. At the suggestion of Fokker, Byrd selected Bernt Balchen as Bennett's replacement on the crew. Balchen, a Norwegian test pilot for Fokker, and former member of Roald Amundsen's airship expedition to the North Pole in 1926, was personally given $500 by Fokker for accepting the assignment, and also was outfitted for the journey by Wanamaker's department store in Paris. The CompetitionNevertheless, a French attempt at the prize was flown by Captains Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, leaving May 8th from Le Bourget airfield in France, headed for New York. The plane, a Levasseur PL-8 biplane, painted with his World War I insignia of a black heart, two burning candles, a coffin, and skull and cross bones, and named l'Oiseau Blanc (French for 'white bird"), set out over the Atlantic Ocean, never to be seen again. On May 11th, the financial backers of Byrd's attempt, including Rodman Wanamaker of the same-named department store, announced that Byrd's airplane would not be allowed to head to Paris until Nungesser and Coli's fate had been determined one way or the other. At that same time, a young and relatively unknown American airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh arrived in New York City from a transcontinental flight in his plane, a Ryan B-1 Brougham named "The Spirit of St. Louis". On the morning of May 20, 1927, Lindbergh flew from New York and, thirty-three and a half hours later on May 22nd, landed safely near Paris, alone and non-stop, claiming the Orteig Prize.  Rodman Wanamaker, the store's president and Byrd's chief backer, however insisted the plane be named, "America", after a Curtiss boat plane he financed for another trans-Atlantic journey years earlier. The "America" was christened in a public ceremony on May 21, 1927, (almost at the same moment that, in France, Lindbergh successfully landed) sponsored by Mrs. Hector Munn and Mrs. Gurnee Munn, the daughters of Rodman Wanamaker. The two women broke over the bow of the plane bottles of water brought from the Delaware River at the point where General Washington crossed with his troops. Also present at the ceremony were Pierre Mory, the French Vice Consul in New York City; Grover M. Whalen, Vice President of the American Trans-Oceanic Company; Harry F. Byrd, Governor of Virginia, and brother of Commander Byrd; as well as Commander Byrd's mother and wife. Looking upon the trans-oceanic flight now as valuable training and scientific experience, and not as a prize-winning venture, Byrd continued his preparations for the flight. Meanwhile, another Orteig contender, the Bellanca monoplane named 'Colombia', piloted by Clarence D. Chamberlin and backed by Charles A. Levine, who was also a passenger on the flight, flew the second non-stop flight across the Atlantic, landing in Berlin, Germany, on June 6th, 1927, after over 42 hours of flight, and having traveled a distance of 3,905 miles. The Flight |

|

The flight crew of "America" from left to right - Lieutenant George O. Noville, Lieutenant Commander Richard E. Byrd, Bertrand Acosta, and Bernt Balchen. This photo was taken shortly after they landed in France. |

Byrd had been delaying the flight, waiting ideal weather, but was marred by some of the worst weather imaginable for flying. After flying out of New England and over Newfoundland, Acosta accidentally lost control of the aircraft, sending her down towards the sea. A last-moment correction from Balchen saved the ship and crew from the cold waters. At one point in the flight, radio troubles developed when Noville's feet became tangled in the wiring of the radio set.

Byrd had been delaying the flight, waiting ideal weather, but was marred by some of the worst weather imaginable for flying. After flying out of New England and over Newfoundland, Acosta accidentally lost control of the aircraft, sending her down towards the sea. A last-moment correction from Balchen saved the ship and crew from the cold waters. At one point in the flight, radio troubles developed when Noville's feet became tangled in the wiring of the radio set.

Through clouds, fog, heavy winds, and rain, the "America" flew out onward to the east, with Byrd scribbling repeatedly in his diary, "Impossible to navigate". At regular intervals, the plane's position was tracked, but as the plane approached the coast of France, the compass begun to malfunction.

'Feet Wet'

After a flight of over forty hours, the airplane managed to arrive over Paris, but was unable to land due to heavy fog, even after 6 hours (and, at observers reported, nearly hitting the Eiffel Tower).

After a flight of over forty hours, the airplane managed to arrive over Paris, but was unable to land due to heavy fog, even after 6 hours (and, at observers reported, nearly hitting the Eiffel Tower).

"I'll never forget those last few moments," said Byrd, nearly twenty years after the event. "It was the most dramatic thing that ever happened to me and that includes the flight over the North Pole and the later trips over the South Pole."

Balchen took the controls of the aircraft, flying the plane 150 miles back to the west and, low on fuel, forced a water landing 300 yards off the shore near Ver-sur-Mer, in Normandy. The tail of the plane became bent, a two-foot wide slash opened in the side of the fuselage, the landing gear became erased from the plane, and the three propellers all broke.

The monoplane finally sunk and settled in the water up to its wing-level, but Balchen saved the lives of the crew, who had to row via a rubber raft stowed aboard to the shore. However, in the process of ditching, Acosta snapped his collarbone.

The monoplane finally sunk and settled in the water up to its wing-level, but Balchen saved the lives of the crew, who had to row via a rubber raft stowed aboard to the shore. However, in the process of ditching, Acosta snapped his collarbone.

"On land," Byrd recalled, "we started knocking on doors in the tiny village in the middle of the night. We looked like bums. Our high school French was lousy. The residents wouldn't believe we had just dropped in from America. They closed doors in our faces. Finally, we convinced the lighthouse keeper that we had just come from New York. He convinced the mayor, and at long last we were welcomed to France."

In fact, for the special trip, Commander Byrd, a retired naval officer, was sworn in as a U.S. Air Mail Pilot before he left on the journey to make all the mail carried aboard the flight official. As a result of the water landing, some of the 150 pounds of airmail letters (some accounts, however, state only 300 letters) were water-soaked in their mail pouches, robbing them of their stamps.

After being plummeted by the rough waves of the sea, the French Navy secured the airframe with several boats, and hauled the "America" closer to shore where it immediately fell victim to souvenir hunters who quickly reduced portions of the fuselage down to its steel frame, but the three engines were quickly recovered to prevent further damage from saltwater, with the rest of the airplane was towed to Cherbourg, where French naval mechanics attempted to salvage the craft. The crew remained in the village of Ver-sur-Mer for one night and left for Paris the next day.

The four-person crew were also greeted in Paris by Gurnee Munn, the 9-year-old grandson of Rodman Wanamaker, and the four were welcomed in matter causing Byrd to state, "France gave us her very best."

|

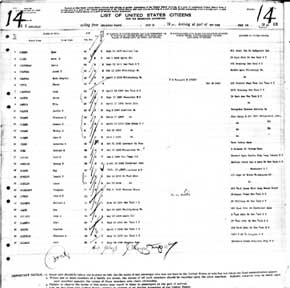

Page 14 of the Passenger List of the Steamship S.S. Leviathan. Click the image to see the names of Byrd, Acosta, and Noville (all highlighted) |

The four men left France aboard the steamship 'Leviathan', the flag ship for United States Lines, along with Clarence Chamberlin, who was returning from his flight from New York to Berlin a month earlier. Back in America, both Byrd and Noville were also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the highest award in the U.S. military for aviation achievements.

Postscript

Richard E. Byrd returned to America a national hero, and a grand ticker-tape parade akin to the one he received just two years prior for his arctic exploits. In 1928, he took two ships and three airplane on his first expedition to Antarctica. On November 29, 1930, he flew, along with three others, the first flight over the South Pole. In total, he mounted four expeditions to the Antarctic, the last being in 1947. He was also responsible for establishing three permanent research station in Antarctica during 'Operation Deep Freeze'., He was ultimately promoted to Rear Admiral in the U. S. Navy, and awarded the Medal of Honor for his service in exploration. He died in Boston on March 11,1957, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 2, Site 4969-1)Bernt Balchen continued to fly with Byrd, and 1929, came the first pilot to fly over the South Pole. During World War II, Balchen was responsible for setting up a training camp for Norwegian expiates near Toronto named "Little Norway", and later in the war, oversaw the construction of the U.S. air base in Thule, Greenland. Promoted to Colonel in the U.S. Air Force, he commanded the 10th Rescue Squadron in Alaska. He retired in 1956, and passed away on October 17, 1973. He is one of the few Norwegian-born people buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 2, Site 4969-2) .

Bertrand Acosta continued to work as a test pilot when, in November of 1936, he flew to Valencia in Spain to head the "Yankee Squadron", aiding the loyalists against Generalissimo Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Returning to America in 1937, he continued to fly until 1946, when his health declined. In 1951 he collapsed and was hospitalized with tuberculosis. He died in a sanatorium in Spivak, Colorado, on September 1,1954 and was buried at Valhalla Memorial Park in North Hollywood, California, under the Portal of the Folded Wings.

George Noville continued to serve with Byrd, and journeyed with him as his executive officer on the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition. He retired from the Navy with the rank of Commander, and he later started an aeronautical engineering consulting firm in Los Angeles. He passed away in January of 1963.

Floyd Bennett recovered from his injuries and continued to fly until April of 1928, when developed pneumonia during a rescue flight with Balchen to Greenly Island, north of Newfoundland, to save the crew of the German airplane "Bremen" which had crash-landed after flying the Atlantic. He died April 25, 1928 in Quebec, Canada, much to the shock of the entire nation. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 3, Site1852-B-E). New York City's first municipal airport was named 'Floyd Bennett Field' in his honor.

The beach where the "America" put down in France later became associated with another America triumph. During the second World War, the beach was given the codename, "Omaha" and was the site where the 29th Infantry Division landed on June 6th, 1944, during D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Choosing a right aircraft seemed to be a simple task for Byrd for he picked a craft he was familiar with. The Fokker C-2 monoplane was chosen as it was a very similar airframe and design to the Fokker F.VII which he had used for his Arctic flight a few years earlier seem a logical choice. The C-2 had three reliable 220hp Wright J-5 engines, the necessary range and plenty of room for his scientific instruments critical to the flight. It was given, by the U.S. government, the tail registration number of NX-206.

Choosing a right aircraft seemed to be a simple task for Byrd for he picked a craft he was familiar with. The Fokker C-2 monoplane was chosen as it was a very similar airframe and design to the Fokker F.VII which he had used for his Arctic flight a few years earlier seem a logical choice. The C-2 had three reliable 220hp Wright J-5 engines, the necessary range and plenty of room for his scientific instruments critical to the flight. It was given, by the U.S. government, the tail registration number of NX-206.