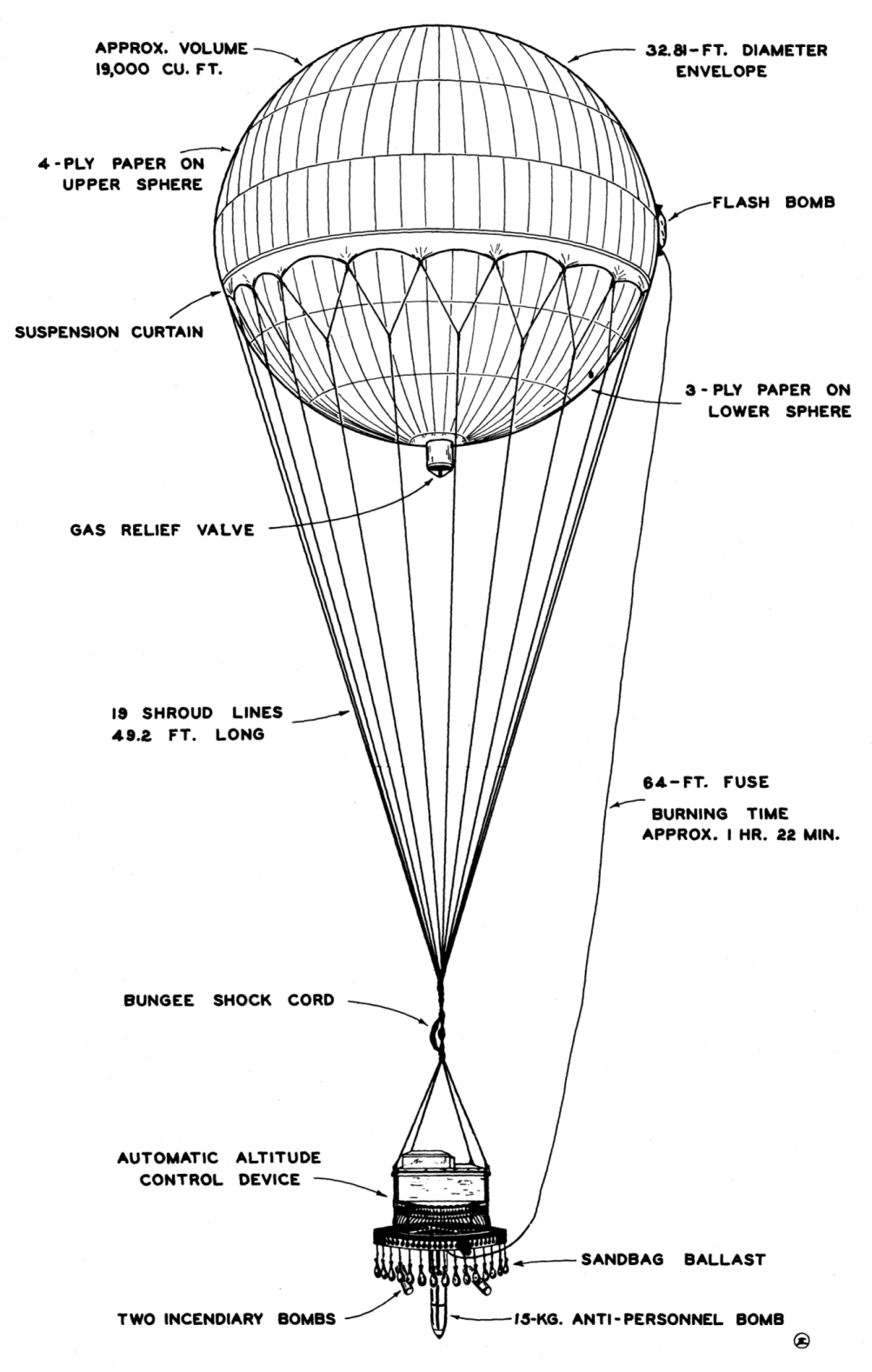

Cherry-Red Shrapnel… The only civilian casualties of World War 2 in the continental United States On Gearhart Mountain, outside Bly, Oregon 5 May 1945  “Project Fu-Go,” also referred to as “The Windship Weapon” by the Japanese military, began in November of 1944 and continued until the end of April 1945. Created by the Imperial Japanese Army's Ninth Army's Number Nine Research Laboratory, under Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, the weapons – conceived initially to gather weather data - measured some thirty feet in diameter with a volume of 19,000 cubic feet. The 150-pound balloon assembly was made of panels of laminated tissue paper made from kōzo bush bark. Workers, often school-age children pressed into industrial work – transformed the bark into small panels that were glued together in three or four laminations using edible konnyaku (devil's tongue) paste, and waterproofed with lacquer. “Project Fu-Go,” also referred to as “The Windship Weapon” by the Japanese military, began in November of 1944 and continued until the end of April 1945. Created by the Imperial Japanese Army's Ninth Army's Number Nine Research Laboratory, under Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, the weapons – conceived initially to gather weather data - measured some thirty feet in diameter with a volume of 19,000 cubic feet. The 150-pound balloon assembly was made of panels of laminated tissue paper made from kōzo bush bark. Workers, often school-age children pressed into industrial work – transformed the bark into small panels that were glued together in three or four laminations using edible konnyaku (devil's tongue) paste, and waterproofed with lacquer.

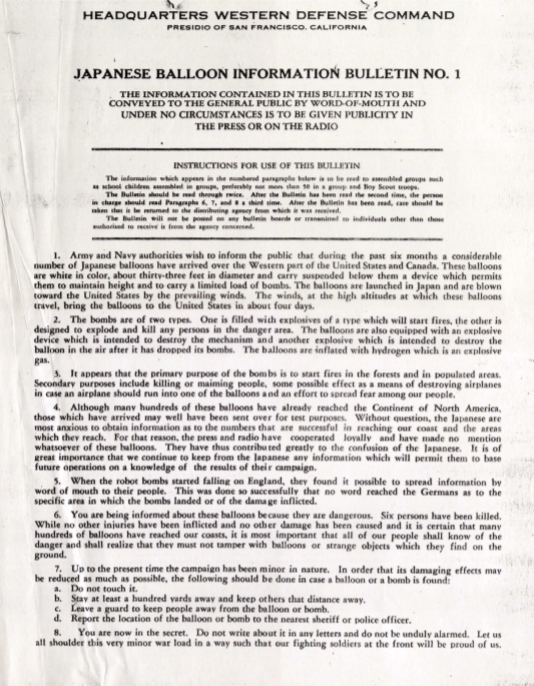

The balloons were launched from three beaches on the eastern coast of the Japanese “home island” of Honshu. Once the balloons were filled with hydrogen gas and launched, they rose to around 30,000 feet to float in the jet stream – a fast-flowing, narrow, meandering air current encircling the Earth. Gas pressure relief valves and a series of paper sandbags were attached to the balloon’s rigging, designed to maintain the proper altitude and flight duration needed to reach the United States. Released by small explosive charges, bags containing high explosives or incendiary thermite were dropped - set off by barometric switches and long-delay fuses. Once over the North American continent, the remaining ballast sandbags would fall to reduce the balloon’s altitude, and the final charges released two 12-kilogram incendiary bombs and a single 15-kg anti-personnel explosive. While the bombs caused little damage, their potential for destruction and fires was huge, as well as their potential psychological effect on the American people. As such, the U.S. strategy was to keep the Japanese from knowing of the balloon bombs' effectiveness. Numerous balloon bombs overflew the U.S. and Canada. Stateside military squadron and the U.S. Forest Service actively combated the threat under the codename "Project Firefly," shooting down dozens, recovering the remains for study, and keeping the whole affair under wraps. At the same time, Japanese propaganda broadcasts falsely announced great fires and the American public in a panic, declaring casualties in the thousands, “to offset the shame of the Doolittle raid.” The media blackout was not total, however. An Associated Press story dated December 18, 1944, stated that the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the military were investigating a paper balloon with incendiary attachments found by a lumberjack and his father in a mountainous, forested region southwest of Kalispell, Montana, on December 11, 1944, with a very detailed description of the curious find. In 1945, Newsweek ran an article titled "Balloon Mystery" in their January 1 issue, and a similar story appeared in a newspaper the next day. The Office of Censorship then sent a message to newspapers and radio stations to ask them to make no mention of balloons and balloon-bomb incidents, as they did not want the Japanese military to learn the balloons could be effective weapons or to have the American people start panicking. Cooperating with the government, the press did not publish any balloon bomb incidents – with the Japanese learning of only one bomb's reaching Wyoming, landing and failing to explode. The effort ended when the cheap pyrotechnic controls used on the balloons failed. That enabled the U.S. to retrieve some of the ones that didn’t self-destruct. But most of the balloons fell short of the coast, falling into the Pacific’s abyss. With no evidence of the weapons’ effect, General Kusaba was directed to cease operations in April 1945, as it was thought the balloons were a waste of time and resources. The expense was considerable and, in the meantime, American B-29 raids had destroyed two of the three hydrogen plants needed by the project. The last fire balloon was launched from Japan in April 1945. In all, the Japanese released an estimated 9,000 fire balloons. At least 342 reached the United States, with some drifting as far as Nebraska. But the press blackout in the U.S. continued. Babes in the Wood  Reverend Archie Emerson Mitchell was born May 1, 1918, in Franklin, Nebraska, and moved with his family to Ellensburg, Washington, in 1939. He attended Simpson Bible College in Seattle, where he met his future wife Elsie Winters. Reverend Archie Emerson Mitchell was born May 1, 1918, in Franklin, Nebraska, and moved with his family to Ellensburg, Washington, in 1939. He attended Simpson Bible College in Seattle, where he met his future wife Elsie Winters.

Elsie M. Winters was born in Port Angeles, Clallam County. Her father, Oscar, worked at the R. M. Morgan sawmill and did carpentry. Her mother, Fanny, maintained the home and raised the children. Following her high school graduation, Elsie went to Seattle and worked as a maid for the family of the noted Seattle libel law attorney Paul Ashley. In 1941 she enrolled in the Simpson Bible Institute of Seattle, the western regional bible school for the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church, where she met Archie. They were married in her home town of Port Angeles on August 28, 1943. Their honeymoon was a trip across the country to Nyack, New York, where they attended a one-year program in missionary work at the Nyack Missionary Training Institute. In March of 1945, the couple began a planned two-year "home service" before their overseas missionary work. They moved to Bly - a town of about 450 people located between Klamath Falls and Lakeview in south-central Oregon - so Archie could become the pastor at the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church. In May of 1945, Elsie was five months pregnant with the couple’s first child. At 8 in the morning on Saturday, May 5, 1945, under a clear blue spring sky, the couple took the boys from their Sunday School class up into the forest on nearby Gearhart Mountain, having baked a chocolate cake for the special occasion. One of the boy’s sisters decided to tag along on the adventure. On the mountain’s south side, however, patches of snow remained on and near Dairy Creek Road (today called Forest Service 34). Traversing the 15 miles into the forest was a challenge, and the Reverend made frequent stops at little streams to test the fishing conditions, catching nothing. Pressing onwards resulting in worsening road conditions, so much so that a road grader blocked the road, having become stuck in a mud hole the day prior. The Reverent pulled his car over to the side of the road to ask the three-person road crew about road and fishing conditions at nearby Leonard Creek. At the same time, Elsie was likely experiencing a bit of motion sickness from the pregnancy and decided to take a walk in the fresh air with the five children. | |  |  |  | | Sherman Shoemaker | Jay Gifford | Edward Engen |  |  | | Joan Patzke | Dick Patzke | | |

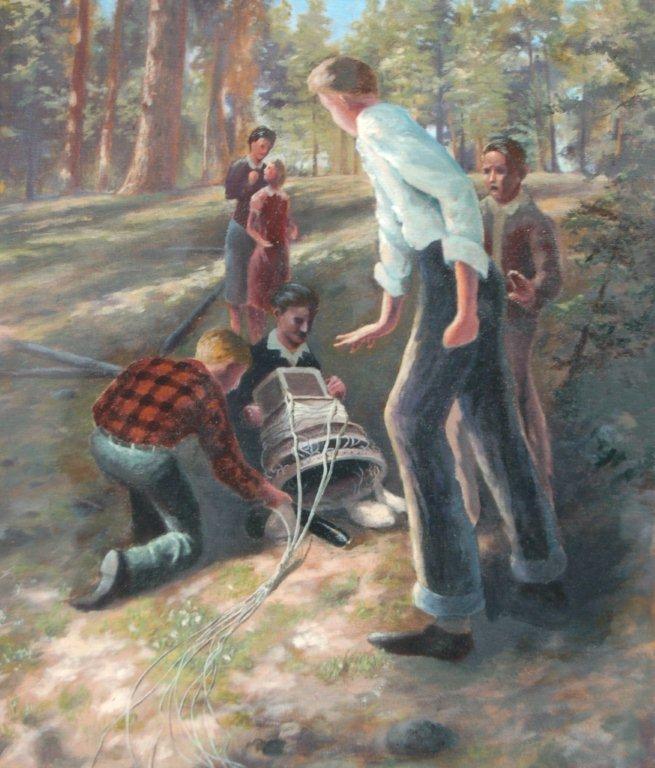

The five children: Sherman Shoemaker, 11, Jay Gifford, 13, Edward Engen, 13, Ethel “Joan” Patzke, 13, and Richard “Dick” Patzke, 14, Sherman was born in Lemoncove, a small town in Tulare County, California. The youngest of six children, his oldest brother, Lee, entered the US Army Air Corps in December 1942, and after basic training, he was transferred to England. After five months, he moved on to France, landing at Omaha Beach about a week after the invasion. Lee was involved in all five of the major European invasions including the Battle of Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge. Jay Gifford was an only son, his father being an oil salesman from Nebraska and his mother, a homemaker from Montana. Edward Engen was also an only son, but of Norwegian immigrants. His father was a logging truck driver and the Scoutmaster of the Bly Boy Scout troop Joan and Dick Patzke were two of the youngest children in a large family – 10 kids in total. Sadly, a few days prior, their family learned the fate of one of their brothers, Jack, who had served in North Africa and Italy as a Radio Operator/Gunner on a B-17G Flying Fortress Bomber. A year prior, on April 30th, 1944, his aircraft – assigned to 99th Bomb Group’s 347th Bomb Squadron, tail number #42-32014, and nicknamed “Pappy Yokum” -was shot down near Bologna, Italy, while on a bombing mission. Jack survived, was captured, and interned at Stalag Luft III at Sagan, Poland. As the German Army was forced to retreat from advancing Soviet forces, the prisoners were marched west towards the heart of Germany. Jack and another airman attempted to escape but were recaptured and executed. Jack’s status was updated to Missing in Action since American forces liberating his fellow prisoners on April 29th did not know the location of Jack.  The work crew led by Richard “Jumbo” Barnhouse, who was operating a Forest Service road grader, was nearby as well. With him were George Donathan and John Peterson. Barnhouse could see the children formed in a semi-circle but couldn’t see what they were looking at. Elsie called out two more times. Reverend Mitchell, who was getting out of the car and bringing the picnic lunch, responded, ‘Wait a minute, and I’ll come and look at it. The work crew led by Richard “Jumbo” Barnhouse, who was operating a Forest Service road grader, was nearby as well. With him were George Donathan and John Peterson. Barnhouse could see the children formed in a semi-circle but couldn’t see what they were looking at. Elsie called out two more times. Reverend Mitchell, who was getting out of the car and bringing the picnic lunch, responded, ‘Wait a minute, and I’ll come and look at it.

At 10:20 that morning, in an apparent act of child curiosity - one of the children, Joan, tugged at or kicked the object. This careless act activated a high explosive charge from the fallen object: a Japanese Fu-go balloon bomb, identified by its main valve number, 5893. A terrific explosion rocked the ground as pine needles, twigs, and branches flew through the air. Barnhouse immediately stopped the grader, which was about 150 yards from the explosion, and both he and Mitchell ran towards the cacophony. Arriving at a large hole nearly 3 feet across and a foot deep, the pair quickly discovered the carnage as four of the children laid dead and badly mangled, while Joan Patzke and Elsie Mitchell remained severely injured. Smoke rose from the Reverend wife’s clothes, which he quickly extinguished, but it was too late. Both of the initial survivors rapidly passed away as well, having never regained consciousness after the explosion. Upon his finding of the scene, Barnhouse jumped in his truck with his co-worker, George Donathan, and raced downhill to the ranger station in Bly, nine miles away. Bursting through the office door, Barnhouse shouted, "There's been an explosion on Gearhart Mountain, and several people are hurt." Rangers Spike Armstrong and timber manager John “Jack” Smith gathered first-aid supplies and headed up the mountain. There, they found the six bloodied bodies, covered in spruce branches by the Reverend and Peterson, near a deflated white paper balloon that was partially buried under a snowdrift. "Spike said to me, 'Can you check their pulse? I don't think I can handle it,' " said Smith. "So I checked. Mrs. Mitchell and the five young people were all dead.” At about 1 o'clock, the sheriff, coroner, and officials from Lakeview Naval Air Station arrived. The men gathered the remains of the two females, who were the two farthest from the debris field. But, out of fear of triggering a secondary explosion – the bodies of the four boys were untouched. A couple of hours later, Army personnel from Fort Lewis, Washington, arrived and began to pick up pieces of the balloon, bombs and mechanism - scattered over an area 90 feet in diameter, with fragments being found up to 400 feet away – to take with them back to Lakeview Air Base. The bomb disposal officer also located and defused four thermite incendiary bombs, a demolition charge, a magnesium flash bomb, and several small plugs each containing a small powder charge. Seeing that the balloon still had snow underneath it, while the surrounding area did not, they concluded that the balloon bomb had drifted to the ground several weeks earlier, and had lain there undisturbed until found by the group. As the evening started, the bodies of the six slain were removed, and – only then – were the parents of the children notified of the day’s tragedy. Forest Service men came the next day and picked up additional small pieces that were sent to Fort Lewis while official statements were taken. It was determined that what detonated was a Japanese-made, a fifteen-kilogram anti-personnel explosive. Days later, on May 8, the Nazi government of Germany formally surrendered. Victory in Europe, or V-E Day, was declared, and the incident was on the path to being forgotten. The coroner, James Ousley, cited the immediate cause of all six deaths as an “explosion of undetermined origin.” On May 9, a mass funeral for four of the children was held in Klamath Falls, with more than 450 people attending. Sherman Shoemaker was buried in the town cemetery in Live Oaks, California, and Jay Gifford was buried at Siskiyou Memorial Park in Medford, Oregon. Three of the children - Edward Engen, and Joan and Dick Patzke - were buried together at the Linkville Pioneer Cemetery in Klamath Falls, Oregon. With the Reverend escorting her coffin, Elsie Mitchell was buried in her hometown at the Ocean View Cemetery in Port Angeles, Washington.  On May 14, 1945, because of the balloon bomb explosion, the government released warnings about their dangers through state educational systems and civic organizations. Before the “Bly incident,” this information was disseminated only by word of mouth and only in the areas affected by the balloons. On May 14, 1945, because of the balloon bomb explosion, the government released warnings about their dangers through state educational systems and civic organizations. Before the “Bly incident,” this information was disseminated only by word of mouth and only in the areas affected by the balloons.

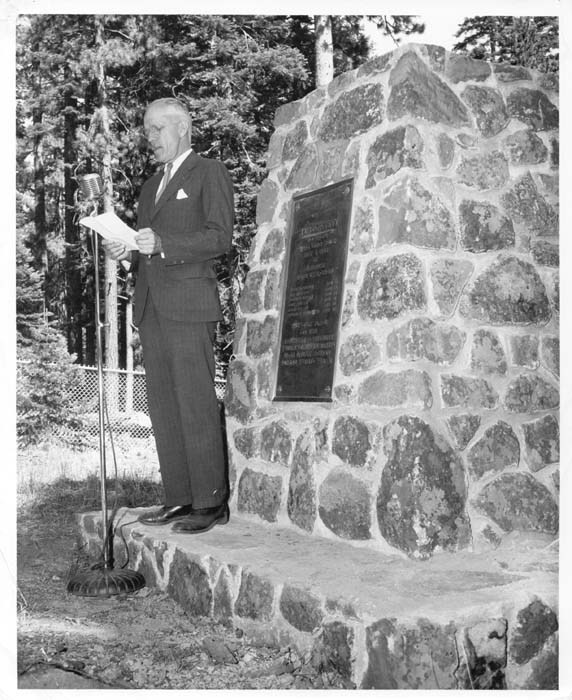

On May 22, 1945, the federal government allowed for the limited publication of very general information regarding the balloons in hopes of preventing further harm to the general public. Several days later, in the June 1, 1945 edition of The Seattle Times, Reverend Mitchell was finally able to share his account of the Bly incident publicly Later, the June 4, 1945, issue of Time magazine ran an article entitled, “Picnickers, Beware” before announcing – a week later – that the May 5th explosion near Bly was a Japanese balloon bomb. After the war ended in August of 1945 with the surrender of Japan, censorship was lifted, and the stories of the balloon incidents were revealed to the public. Jack Patzke was officially declared dead on May 1st, 1946. His remains were later recovered and reinterred in the U.S., next to his siblings, who died in the balloon bomb explosion. Reverend Archie Mitchell continued to minister at the C&MA church for many years and eventually married Joanne “Betty” Patzke the older sister of Dick, Joan and Jack, on June 1st, 1947. In the aftermath of the explosion, Reverend Mitchell told his new wife that ``he felt like Job of old,″ a reference to the biblical figure. "All were taken, and he alone was left to tell the story. He said, `The Lord gives and the Lord taketh away,” the second Mrs. Mitchell recalled in an interview with the Associated Press years later, adding ``he never once showed bitterness at all towards the government, or the military, or the Japanese.″  | | Edmund Hayes, Vice President of the Weyerhaeuser Company, speaks at the Mitchell Monument dedication |  | | The parents of Elsie Winters Mitchell look at the monument's plaque |

On the other side of the country, restitution for the balloon bomb’s victims was first introduced by Representative William Lemke of North Dakota. Senator Guy Gordon of Oregon and other proponents of the measure said that the public had not been warned of the danger from the airborne bombs, although the armed services knew that several had reached this country. On June 7, 1949, Private Law 81-92 was approved. It authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to pay claims to the families of each child, and Archie Mitchell, for their losses. The families of Edward Engen, Jay Gifford, and Sherman Shoemaker each received $3,000, Archie Mitchell received $5,000 for the loss of his wife, and the parents of Richard and Ethel Patzke received $6,000. In 1949, Tom Orr, a branch forester for Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, designed the monument and recreation area. On August 20, 1950, the company dedicated a memorial to those killed by the bomb. The monument, constructed of native basalt and stone, displays a bronze plaque bearing the names of the victims. Oregon's governor Douglas McKay spoke at the ceremony, which saw 300 in attendance, including Elyse’s parents and the families of all five children, and remarked that the six were war casualties “just as surely as if they had been in uniform.” Reverend Mitchell and his second wife, Betty, were not in attendance, however. A few years after they were married, they became missionaries and went to French Indo-China (now Vietnam). After serving there for a few years, they were working at the Ban Me Thuot Leprosarium, treating lepers, when Viet Cong soldiers raided it on the evening of May 30, 1962. The Viet Cong soldiers seized three Americans—Dr. Eleanor Ardel Vietti, Reverend Mitchell, and Daniel Gerber, a 22-year-old volunteer— and looted the facilities for supplies. Mitchell’s wife and their four children were spared only because the three others agreed to cooperate. Hopeful for her husband’s return, Betty Mitchell stayed at the leprosarium until she was taken captive again in 1975, along with six other missionaries, by the Viet Cong. Those seven were released ten months later. But Archie Mitchell, Dr. Vietti, and Daniel Gerber are still listed among the 17 American civilians who went missing during the Vietnam War, with no one knowing his fate. After her release, Betty Mitchell returned to teaching, this time in Penang, Malaysia. She became involved in prison ministries and visited Vietnamese refugee camps in Malaysia and Thailand. In 1976, Sakyo Adachi, a Japanese scientist who helped plan the balloon offense, visited the site and laid a wreath at the monument. He later sent a letter of apologies to the Patzke family for the loss of their two children. Betty Mitchell returned to the United States in 1986 and ministered to Dega communities from Vietnam who had relocated to North Carolina. In 1995, Japanese students sent 1,000 paper cranes, a Japanese symbol of peace and healing, to the families of the victims, along with six cherry trees. Later that year, over 500 people attended the 50th-anniversary re-dedication ceremony at the Mitchell Monument site, where the trees were planted. In 1998, the memorial site and its land were turned over to the federal government to be merged into the Fremont National Forest (now the Fremont-Winema National Forest). A small picnic area was developed around the monument and site, now part of the Mitchell Recreation Area and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Click here to see the Forest Service's brochure on the memorial In April of 2005, a Ponderosa pine tree, scarred by the balloon bomb’s shrapnel, was recognized as an Oregon Heritage Tree. It today still bears visible damage from the blast. While primarily considered a military failure, hundreds of potentially dangerous balloon bombs may still lurk in remote, rugged locations of the West. In October of 2014, a pair of loggers in the Monashee Mountains near Lumby, British Columbia, Canada, found the remnants of a balloon bomb. They were later demolished in a controlled explosion. Betty Janet Patzke Mitchell passed away on June 28, 2017. The Methodist church is Bly is today named the "Standing Stone Church of the Christian and Missionary Alliance." In 2018, a significant remnant of the Bly bomb – a segment of red silk shroud – was donated to the Klamath County Museum. Historians have not produced a full scientific explanation for balloon bombs' collective failure. However, the environmental and physical conditions that prevailed during the time support the theory that they were simply “rained out” as the winter of 1944-45 was one of the wetter one on record for the western United States. |