Near Al Mayadin, Syria

June 19, 1947

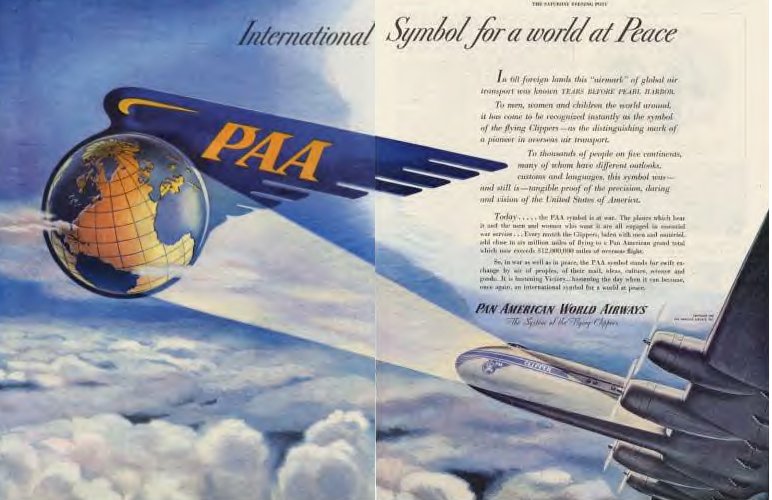

Service – Around-the-World

It was the beginning of round-the-world service for Pan American Airways, and the airline brought in, for the flight, some of its finest crew. On the leg from Karachi, India, to Istanbul, Turkey, designated Flight 121, the New York City based flight consisted of ten Pan-Am personnel: Captain Joseph Hall Hart, Jr., First Officer Robert Stanley McCoy, Second Officer & Navigator Howard Thompson, Third Officer Eugene W. Roddenberry, First Engineer Robert B Donnelly, Second Engineer W. E. Morris, First Radio Officer Nelson C. Miles, Second Radio Officer Arthur O. Nelson, Purser Anthony Volpe, and Stewardess Jane Bray.

Captain Hart, who was born April 10, 1905, and was noted for setting a world record in January of 1945, when he completed 12 trips across the South Atlantic in 13 days and 15 hours. A graduate of the University of Cincinnati in 1930, he attended the Air Corps flying school until 1931. He became a captain in 1935 and a master pilot in 1941, and had over 12,000 hours of flight time logged, with over 1,000 of those being in a Constellation.

Hart's first officer, 25 year-old Robert Stanley McCoy of Flushing, Long Island, New York, was co-pilot of the aircraft at the time of the accident and possessed an airline transport pilot rating. He had accumulated a total of 3,178 hours, of which 674 had been in Constellations.

The "Connie"...

The Lockheed Constellation for the westbound flight was registered as NC-88845, and christened the “Clipper Eclipse” by Pan-Am. It had been operated a total of 2,645 hours since original manufacture, and was equipped with four Wright 745C18BD3 engines, with Hamilton Standard propellers. Unusual to this plane, however, was the fact that is had previously had the name “Clipper Dublin” when it was delivered to Pan-Am in February of 1945. The renaming of a vessel is generally considered bad luck. And, earlier that week, the “Clipper Eclipse” was forced to turn back at Gander, Newfoundland, on the trans-Atlantic flight after developing engine trouble delaying it two days.

Flight 121 departed from Karachi at 3:37 PM on June 18, 1947, for a return trip to the United States. The climb to the cruising altitude of 18,500 feet was routine, and the flight was proceeding direct to Istanbul, the first intended point of landing, estimating its arrival there to be 2:08 the next morning. However, five hours after take-off, trouble developed in the number 1 engine – the result of the number 18 exhaust rocker arm breaking as a result of fatigue - and the number 1 propeller was feathered. When the flight's stewardess, Jane Bray, went to sleep on the flight, she knew that one motor was feathered, but she was unworried about it.

Due to closed airports and inadequate repair facilities, Captain Hart decided to continue to Istanbul with the use of three engines. However, it soon became evident that at an altitude of 18,500 feet, the airspeed obtainable was not sufficient to provide adequate cooling for the engines. even though climb power was applied. The power from the remaining three engines was reduced, and altitude was gradually lost. At 17,500 feet, the engines were still overheating, and so the descent was continued downwards to 10,000 feet.

Drifting Downwards...

At 9:40 PM, about one hour after the failure of engine number 1 – the outermost port-side powerplant - the flight advised its company radio in Karachi of the engine trouble, and reported its position, at 14,000 feet, 50 miles east of Bagdad, Iraq, and 90 miles east of the Royal Air Force Field at Habbaniya, Iraq, at 10 PM.

Shortly after the 10PM report however, Habbaniya Tower was advised by the the crew of Flight 121 that its approximate position was over Bagdad at an altitude of 10,000 feet, and the flight requested Habbaniya Tower to inform the civilian airfields in their area that the aircraft was proceeding with the use of only three engines to Istanbul. Habbaniya Tower replied, stating that no airfields would be open until dawn, and suggested that an emergency landing be made at Habbaniya. Flight 121, however, affirmed its intention to continue, and added that if it were impossible to reach Istanbul, a landing would be made at Damascus, Syria. At 10:25, Habbaniya Tower answered hat all airfields in the Damascus area were closed until 4 AM and again suggested that the flight land at Habbaniya. The flight again stated that it would continue to Istanbul, but that it would turn back to Habbaniya if they experienced any more trouble.

At the same time, Flight 121's crew sent a message, received in Karachi, and relayed to Damascus, requesting that Damascus Radio be alerted to stand by, and that the airport be opened. At 11:08 PM, Damascus Radio was on the air, and the field was opened to handle any anticipated emergency.

Flight 121, at about 11 PM, reported its position to be 75 miles northwest of Habbaniya at 10,000 feet. But, about twenty minutes later, the flight's purser, Anthony Volpe, who seated in the passenger cabin noted that the "Fasten Seat Belt – No Smoking” sign had been illuminated. He immediately started to awaken the passengers so that they might fasten themselves in their seats.

Fueled by Streamslip...

Without warning, the entire cabin became lit from a fire which had started in the number 2 engine nacelle – also on the plane's port side. Evidentially, the engine's thrust bearing failed, which in turn resulted in blocking the passage of oil from the propeller feathering motor to the propeller dome. The report of this fire was received at 11:30 PM by the Habbaniya direction finding station, at which time the flight was reporting a position of 170 statute miles northwest of Habbaniya, and 290 miles northeast of Damascus.

A short time later, stewardess Bray was awakened by flames whipping past the port windows. She saw the purser, Anthony Volpe, and the third officer, Eugene W. Roddenberry, standing in the aisle.

"I knew then it was bad. They came to me and said 'Get your belt fastened tight.' Then all of us called to the passengers to get their belts on. They did. There was not a sign of panic. Nimbalkar Rajkumar, the Indian prince, got up and went over to his mother, the Rani. Everybody I see sat still and we just waited, each thinking his own thoughts.”

Immediately after the fire started in engine number 2, a rapid descent was made for the purpose of crash landing the aircraft, and several minutes later, on the landing approach, Bray recalled, "I looked out. The number 2 motor was all afire and it seemed to have spread to the wing. I wondered why they didn't drop that motor. I looked up and even through the fire I could see bright stars. But everything else was black as pitch. Suddenly there was a hard jar, just like when a tooth is pulled and you feel it crunch. The burning motor had fallen loose.”

From Bad, to Worse...

The wing near the number 2 engine, however, continued to burn intensely. Less than a minute after the number 2 engine fell from the aircraft, a wheels-up landing was made on relatively smooth, hard-packed desert sand near the banks of the Euphrates River, near the Syrian town of Al Mayadin, near the Iraqi border.

The left wing tip made the first contact with the ground, then the number 1 propeller and then the left wing at the number 2 engine position. The impact tore the left wing from the fuselage near its root, and caused the aircraft to ground loop violently to the left. According to stewardess Bray, "We hit hard on the belly with an awful jar which would not stop. We slid across the sand. The plane swung hard around to the left and split in two, pretty well forward. Flames poured in and the heat became terrific.”

During the course of the ground loop, the aircraft turned 180 degrees, skidded backwards for a distance of 210 feet, then came to rest in flames 400 feet from the first point of impact - pointed opposite to its direction of landing.

Dr. Randen Ahmed of Calcutta, said that "both sides of the plane blew off and that explains how some passengers were saved."

The flight's Third Officer, Eugene Wesley Roddenberry, of River Edge, New Jersey, purser Anthony Volpe and stewardess Jane Bray helped evacuate the wrecked airliner - "We who could jumped out. The other survivors were handed clown and we dragged them away and tried to do what we could for them. We had to carry the Rani away. She had a head injury and had lost some teeth and was in a rather bad way, but we finally quieted her.”

Bray recalled, "All we could do then was watch while the plane burned, slowly at first and then fiercely. It must have burned for hours, but I do not remember too well. There wasn't any sound but those flames. Everybody who died must have been killed outright."

A Ready-made Disaster...

Fifteen persons of 37 aboard - eight passengers and seven crew members – were killed in the crash and fire. The remaining 19 passengers and 3 crew members were relatively unharmed.

Roddenberry, who flew 89 combat bomber missions in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, phoned in a report of the crash from Deir-Ez-Zor. Juan Trippe, president of the Pan American, received a report of the accident upon his arrival at Istanbul of the “Clipper America” on the round-the-world flight of American editors and publishers. Trippe planned to send an emergency plane to the scene of the crash, although physicians and nurses already were at the scene. The newspaper reporters and publishers passed up an official program prepared in their honor, and stayed at a midtown Istanbul hotel to await full details of the accident.

After the Embers...

The Civil Aeronautics Board determined that the probable cause of the accident was a fire which resulted from an attempt to feather the number 2 propeller after the failure of the number 2 engine thrust bearing.

The “Clipper Eclipse” name was reused, in 1950, on a Pan-Am owned Boeing 377, registered as N90948. Then on a Douglas DC-7C, N746PA, a Boeing 707-321B in 1965, N409PA, and lastly, a Douglas DC10-10, N63NA, in 1980. Pan Am collapsed in 1991.

Roddenberry, after the experience, left Pan Am and aviation in 1948, to pursue a career in Hollywood. He was known to embellish his story of survival, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone to call for help.

While working in his free time to establish himself in the field, in order to provide for his family, he joined the Los Angeles Police Department in February of 1949. He became a Police Officer in 1951 and was made a Sergeant in 1953. But, on June 7, 1956, he resigned from the police force to concentrate on his writing career.

In 1964, Roddenberry made a proposal for the original TV series to NBC, described as a "Wagon Train to the stars." The show's first pilot, "The Cage," starring Jeffrey Hunter as Enterprise Captain Chris Pike, was rejected by the network, however, NBC executives were still impressed with the concept and made the unusual decision to commission a second pilot: "Where No Man Has Gone Before".

The show's name - "Star Trek".