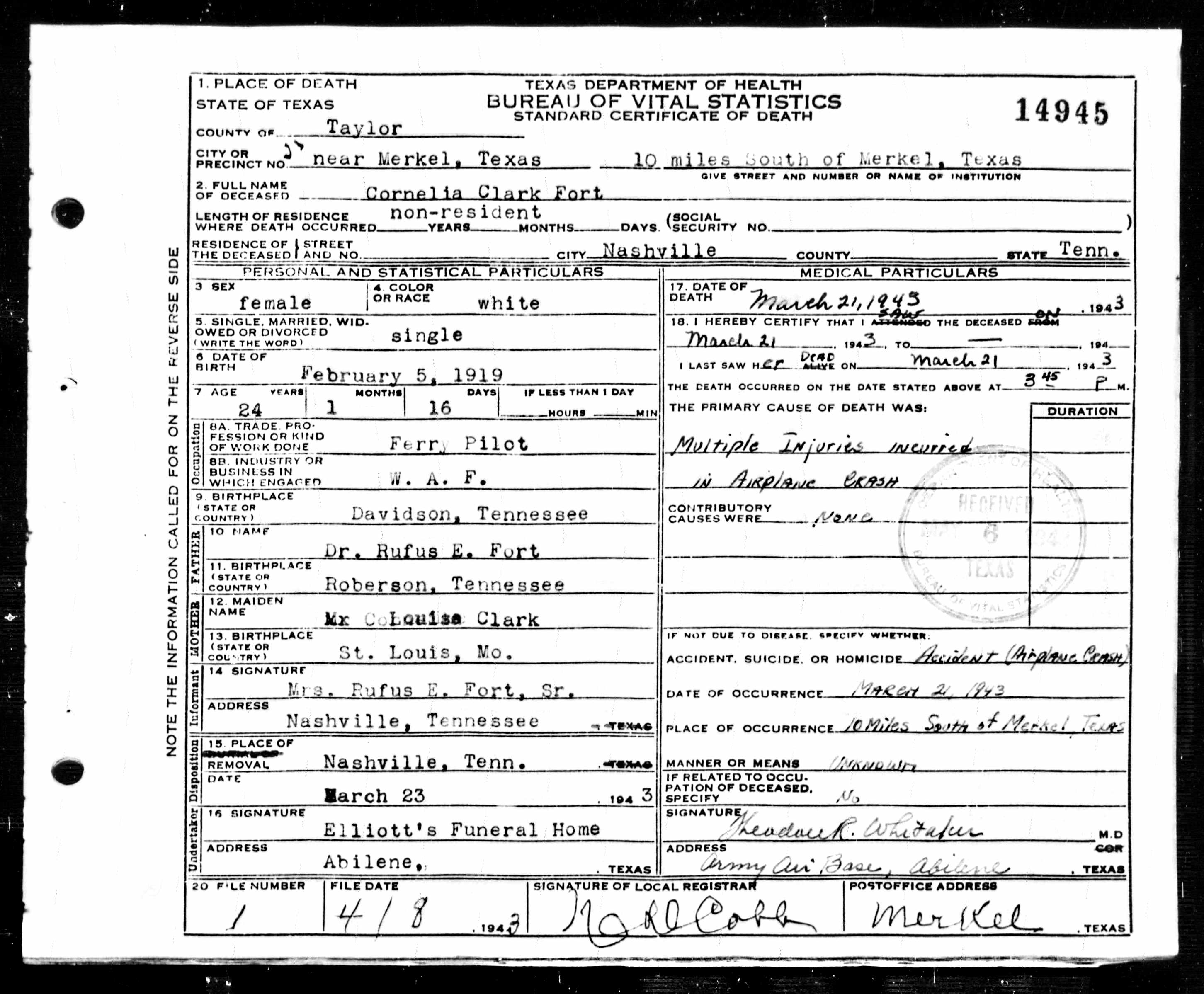

The Epic of Cornelia Fort… First Survivor at Pearl Harbor - First Women Airforce Service Pilot fatality Near Nubia, Texas March 21st, 1943 Cornelia Clark Fort was born on February 5th, 1919, as the only daughter of a prominent Nashville family; her father, Doctor Rufus Elijah Fort, was a founder of National Life & Accident Insurance Company, based in Tennessee.  Cornelia and her four brothers grew up in a luxurious 24-room mansion, built in 1815 and standing on 365 acres of land on the banks of the Cumberland River in Davidson County, Tennessee. Being privileged, a chauffeur drove the children to private schools, attended societal functions, frequented the Belle Meade Country Club, and lived in relative extravagance. When she was five, her father, who thought that flying was dangerous, made her brothers swear an oath on the family’s Bible never to fly. Cornelia and her four brothers grew up in a luxurious 24-room mansion, built in 1815 and standing on 365 acres of land on the banks of the Cumberland River in Davidson County, Tennessee. Being privileged, a chauffeur drove the children to private schools, attended societal functions, frequented the Belle Meade Country Club, and lived in relative extravagance. When she was five, her father, who thought that flying was dangerous, made her brothers swear an oath on the family’s Bible never to fly.

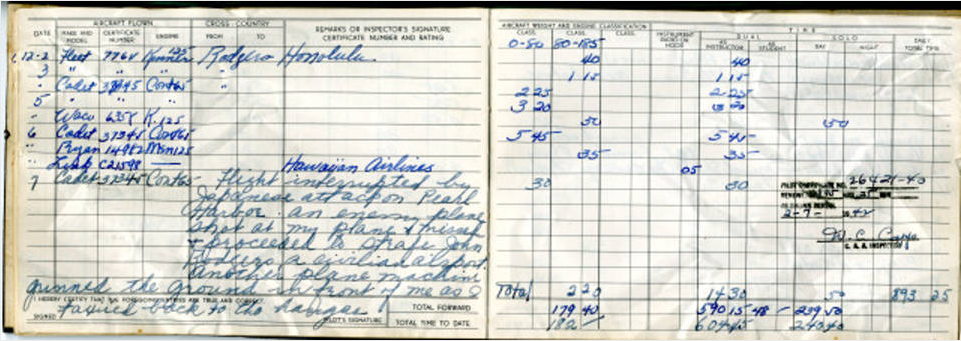

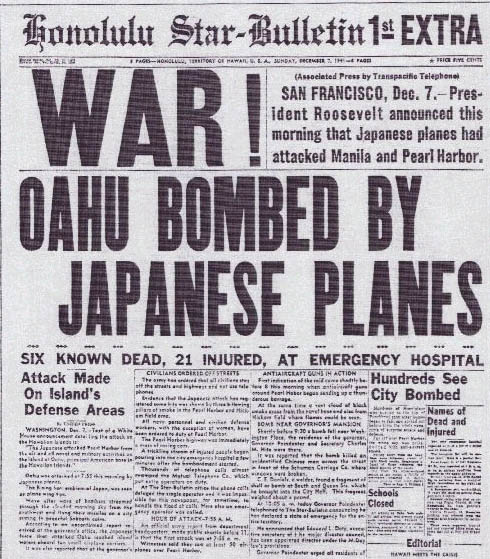

She traveled to Bermuda for spring break in 1938, graduated with an associate’s degree from New York’s Sarah Lawrence College in 1939, and returned home, joining the Junior League of Nashville. But, after her father died in March of 1940, Fort took her first flying lesson in a Luscombe 50 with a friend, Jack Caldwell. She was instantly addicted, and although she could never quite articulate why she loved flying so much, her sister would later state that it was quite simple: Cornelia was, as Louise observed, "a great rebel of her time." Fort learned to fly in Nashville and experienced her first solo flight on April 27, 1940. She earned her private pilot's certificate on June 19, 1940, her commercial license in February of 1941 - becoming the second Nashville woman to do so, and a month later received her instructor’s rating on March 10, 1941. She first took a job teaching for local flyer Garland Pack, and then accepted a position with the Massey and Rawson Flying Service of Fort Collins, Colorado (who offered the job to her not knowing she was a woman) – teaching students taking part in the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP). An avid spokesperson for women in aviation - as the Second World War raged in Europe and American involvement became more likely; she once told a local newspaper, “Women are needed in aviation and can be vital to national defense. Women can do for this country what they are already doing in England… ferrying planes from factories to airports, flying the mail, doing transport work for the government. Every woman who flies releases a man to fight.” In the late summer of 1941, she was hired to teach defense workers, soldiers, and sailors to fly in Hawaii at Honolulu’s Andrew Flying Service. She left from Los Angeles on September 20 on the S.S. Mariposa, arriving in Honolulu on the 25th. Olen V. Andrew, a Honolulu linotype operator, had purchased an unused Stinson cabin monoplane at a sheriff’s sale in Hawaii, founded the Andrew Flying Service, and started barnstorming. Carrying sightseers for one cent a pound and half a cent more for inter-island flights, he leveraged his earnings, bought more airplanes, and transformed his operation into a flying school. In November, in a letter home to her brother, she wrote: "If I leave here I will leave the best job that I can have (unless the national emergency creates a still better one), a very pleasant atmosphere, a good salary, but far the best of all are the planes I fly. Big and fast and better suited for advanced flying." Front Row Seat to Disaster – December 7th, 1941 By early December, Fort was flying on a daily basis. Early on the morning Sunday, December 7th, and with her regular student – Ernest Suomala – she took off from John Rodgers Airport in Honolulu, northwest of Pearl Harbor, aboard an Interstate S-1A ‘Cadet,' serial number 188 and bearing tail number N37345. Suomala - a 31-year-old native of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and employed as a machine shop pattern maker for the government - was far enough in his training in the high-wing monoplane to fly regular take-offs and landings in preparation for his first solo flight. The airfield was named in honor of aviator John Rodgers, a naval commander and was Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics until - on August 27, 1926 - the plane he was piloting unexpectedly nose-dived into the Delaware River, killing him. With Suomala at the controls, Fort noticed a fast-moving aircraft approaching from low, over the sea. At first, that didn't hit her as abnormal, as military aircraft were a common sight in the skies above Hawaii. But – as the distance narrowed - she realized this plane was different and that it had set itself to ram her! She plied the controls from Suomala’s grasp and managed to pull the plane up just in time to avoid a mid-air collision. As she would later recount, the plane “passed so close under us that our celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to see what kind of plane it was. The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.” In the haze, less than a quarter mile away, Fort saw the billowing, inky, smoke of burning fuel oil rising over Pearl Harbor. As she recalled, “then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it down, down, and even with knowledge pounding in my mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middle of the harbor. I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a shadow passed over me, and simultaneously bullets spattered all around me,” as nine A6M2 ‘Zero’ fighters from the Japanese carrier ‘Akagi,' led by Lt. Commander Shigeru Itaya, strafed her plane. A pursuing Zero strafed her plane and the runway as she and Suomala for cover. The attackers hit a loaded Hawaiian Airlines DC-3, setting it ablaze, but no one aboard were struck by the bullets. Fort flew the nimble Cadet trainer onto the ground as quickly as she could, taxiing it straight into to the Andrew Flying Service hangar, as bullets sped down in front of her. She and her student leaped from the aircraft and dashed to Andrew’s office, where Fort’s shout of “The Japs are attacking!” was met with disbelief. Seconds later, another person – a mechanic - ran in from outside, yelling, “That strafing plane that just flew over killed Bob Tyce!” The airport manager - Robert Tyce, the owner of the K-T Flying Service – had been killed. Two other civilian planes on instructional flights would also not return that morning. Fort claimed - “Later, we counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.” Afterward, the Zeros broke off their attack on the airfield to chase a formation of 12 unarmed B-17s, arriving in Hawaii after a nearly 14-hour flight from the U.S. mainland, about to land at Hickam Field on their way to the Philippines. On the left-hand side of page 13 of her pilot logbook, Fort wrote the entry for her flight: “Cadet 37345, Cont. 65—Flight interrupted by Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. An enemy airplane shot at my airplane and missed and proceeded to strafe John Rodgers, a civilian airport. Another airplane machine-gunned the ground in front of me as I taxied back to the hangar.”

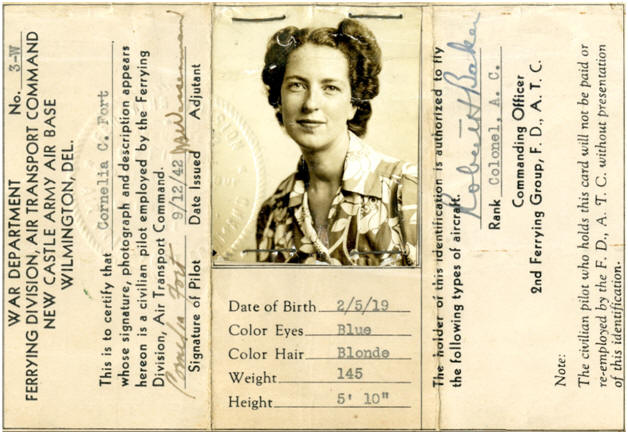

Return to Stateside, and Service...  With all civilian flights suspended in Hawaii, Fort returned to the continental U.S. in early 1942 and quickly found her employment options in aviation limited due to – in part - the wartime rationing of fuel. But, an invitation via telegram dated January 24, 1942, arrived at her home in Nashville from Jackie Cochran, inviting Fort to join a hand-picked group of American women to fly as members of the Royal Air Force’s Air Transport Auxiliary in Britain - a civilian service tasked with the delivery of aircraft from factories to the squadrons of the RAF and Royal Navy, as well as delivering supplies. But Fort was unable to accept the offer - as she wasn't back on the mainland in time. Regardless, she still found ways to contribute, making a short movie promoting War Bonds that was successful, which led to speaking engagements. She resorted to continuing to teach CPTP students, as the need for trained American pilots was greater than ever. However, she still sought to serve her country more directly.  In September of 1942, she received a telegram from Nancy Love, inviting her to join and fly in the newly established Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS). The predecessor to the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), WAFS ferried military planes from their production factories to military bases within the United States. As Fort told a news reporter, “Women are needed in aviation and can be vital to national defense. Women can do for this country what they are already doing in England… ferrying planes from factories to airports, flying the mail, doing transport work for the government. Every woman who flies releases a man to fight.” In September of 1942, she received a telegram from Nancy Love, inviting her to join and fly in the newly established Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS). The predecessor to the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), WAFS ferried military planes from their production factories to military bases within the United States. As Fort told a news reporter, “Women are needed in aviation and can be vital to national defense. Women can do for this country what they are already doing in England… ferrying planes from factories to airports, flying the mail, doing transport work for the government. Every woman who flies releases a man to fight.”

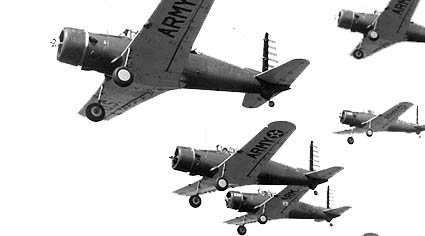

Meeting the requirements of having logged 500 hours and holding a commercial pilot’s license, Cornelia enthusiastically joined as the second woman accepted into the service – arriving in October of 1942 at New Castle Army Air Force Base in Wilmington, Delaware, as part of the original 30 in the WAFS. The military provided the women with ground training but no flight time, as they were all already accomplished pilots. As such, they either passed or failed their graduation flight check. Despite the challenge – 28 passed and were assigned to operational duties, and Fort was sent to the 6th Ferrying Group’s base at Long Beach, California  Describing the sense of pride, Fort wrote – in a piece published in the July 1943 edition of ‘Woman's Home Companion’: “Suddenly and for the first time we felt a part of something larger. Because of our uniforms which we had earned, we were marching with the men, marching with all the freedom-loving people in the world. And then while we were standing at attention a bomber took off followed by four fighters. We knew the bomber was headed across the ocean and that the fighters were going to escort it part of the way. As they circled over us I could hardly see them for the tears in my eyes. It was striking symbolism and I think all of us felt it. As long as our planes fly overhead the skies of America are free and that's what all of us everywhere are fighting for. And that we, in a very small way, are being allowed to help keep that sky free is the most beautiful thing I have ever known.” Describing the sense of pride, Fort wrote – in a piece published in the July 1943 edition of ‘Woman's Home Companion’: “Suddenly and for the first time we felt a part of something larger. Because of our uniforms which we had earned, we were marching with the men, marching with all the freedom-loving people in the world. And then while we were standing at attention a bomber took off followed by four fighters. We knew the bomber was headed across the ocean and that the fighters were going to escort it part of the way. As they circled over us I could hardly see them for the tears in my eyes. It was striking symbolism and I think all of us felt it. As long as our planes fly overhead the skies of America are free and that's what all of us everywhere are fighting for. And that we, in a very small way, are being allowed to help keep that sky free is the most beautiful thing I have ever known.”

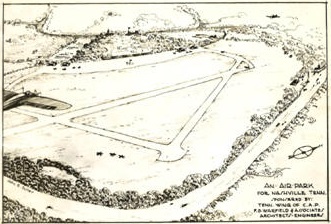

But the flying jobs the WAFS were given were often less glamorous. Fort frequently found herself flying in open-cockpit planes in inclement weather without a radio, as many of the planes, though ground tested, had never been flown before and had austere equipment. The conditions forced the pilots to navigate using basic skills, comparing maps with landmarks they could see below them, rather than more advanced methods using radio frequencies. But she kept a sense of humor, writing home to detailing the flying: “We wear heavy cumbersome flying clothes and a thirty-pound parachutes. You are either cold or hot. If you are female your lipstick wars off and your hair gets straighter and straighter. You look forward all afternoon to the bath you will have and the steak. Well, we get the bath but seldom the steak. Sometimes we are too tired to eat and fall wearily into bed.” End of the Line… On March 21, 1943, Fort flew as part of a six-plane formation from Long Beach to Love Field in Dallas, Texas. During the flight - after an overnight stop in Tucson, Arizona, and fuel stop in Midland, Texas, - they flew in close formation, which was not allowed during ferrying missions, for a portion of the trip. A fellow WAFS pilot, Adela Riek Scharr, would later relate the events of that flight: “Some of [the male pilots] began teasing her and then they began to pretend that they were fighter pilots. She was easy game for them, for she had never had any evasive training in military maneuvering. By the time they got to Texas, a few of the men has become too bold and were flying too close. A joke had become harassment.” At some point after the formation departed their refueling stop of Midland, Texas, most had returned to safer distances within the formation. But, around 3:30 in the afternoon, one of the planes – tail number 42-42450 – piloted by Flight Officer Frank E. Stamme, who had 267 flight hours, collided with Cornelia's plane, BT-13A tail number 42-42432. Scharr wrote, “She zigged when he guessed she would have zagged, and he snagged her.” His landing gear and the tip of Cornelia's left wing crashed together. The wooden tip broke away along with six feet of the metal leading edge. Her plane eventually hit the ground in a vertical position ten miles south of Merkel, Texas, near the hamlet of Nubia, with the aircraft’s engine plowed two feet into the pasture land of Whit Richey. The veteran Fort – with over 1,100 flight hours of experience – was unable to bail out. At only 24 years old, she became the first WAFS fatality, and the first woman pilot to die on active duty in American history. Local farmer Clyde M. Latimer and his wife, Carrie, were standing in a nearby field as their heard Fort’s plane crash. They, along with farm hand Joe Snyder, ran to the crash site, but quickly realized there was nothing that could be done. They stood watch over the wreckage as they awaited for Army investigators to arrive. At the crash site, investigators stated, “the impact of such a mid-air collision could have jammed or damaged the canopy, making it impossible to open and causing the pilot to lose consciousness.” Ultimately, the cause of the crash was given in the official Army report as “momentary lapse of mental efficiency,” and did not assign blame to any of the pilots involved. Aftermath... Fort’s funeral was held at Christ Episcopal Church in Nashville, with flowers given from more than 200 people, including Tennessee Governor W. Prentice Cooper, and her commanding officer, Nancy Love. She was buried in the city’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. The footstone of her grave is engraved "Killed in the Service of Her Country." Love sent a compassionate letter to Fort’s mother, stating: "My feeling about the loss of Cornelia is hard to put into words -- I can only say that I miss her terribly, and loved her...If there can be any comforting thought, it is that she died as she wanted to -- in an Army airplane, and in the service of her country." The Cornelia Fort Airpark in her hometown of East Nashville, which opened in 1945, was named after her. Norman Thomas purchased 200 acres along a bend of the Cumberland River and, because the property adjoined part of a farm owned by Cornelia’s father, Rufus, the name choice was apt. Her own words on an historical marker at the site simply and modestly sum up her wartime contribution: "I am grateful" she wrote, "that my one talent, flying, was useful to my country." John Rodgers Field would later become Naval Air Station Barbers Point, and transform into Honolulu International Airport until the Navy withdrew and closed the base in the 1990s. It was later reopened as Kalaeloa Airport in 1999 - although some still call in Rodgers Field. Cornelia Fort was portrayed in the 1970 film “Tora, Tora, Tora” by then-49-year-old Jean Marie “Jeff” Donnell in the role of the 21 year old. Fort and Suomala’s closed-cabin Interstate Cadet monoplane was depicted as an open-cockpit Stearman Kaydet biplane. In August of 1943, the WAFS was merged with the Women's Flying Training Detachment to create the Woman Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), and flew flew over 60 million miles in every type of military aircraft produced during the war. Unfortunately, by the end of the war, 38 women - including Fort - gave their lives in the service of their nation. The WASP program was deactivated in December of 1944. But the WASP would not be recognized as an official military organization until March of 1979, when their status as veterans, and the requisite benefits associated with that recognition, was conferred. Around the same time - more than 30 years after the WASP flew in World War II - women were finally permitted to attend military pilot training as regular members of the United States Armed Forces. In 1978, the first academic study of the WASP program was undertaken as the subject of a master's student thesis at Washington State University. The writer, Natalie Stewart-Smith, conducted numerous interviews with surviving pilots and leaders, including Jacqueline Cochran. Fort’s student the morning of the Pearl Harbor attack, Ernest E. Suomala, did continue in his flight training, and earned his private pilot certificate. He passed away in on December 19, 1992 in Rochester, Michigan at the age of 82. Army aviatior Frank E. Stamme survived the war, leaving the service in 1947, and became a commercial pilot. He passed away in February of 1987 at 67 years old. A memorial plaque was erected in 2000 at the crash site of Fort’s plane. It is located on private property in Mulberry Canyon, Texas. The state of Texas also erected a historic interpretative marker near the crash site in Merkel, regaling the story of Cornelia Fort. On July 1, 2009, President Barack Obama signed Public Law 111-40, awarding the WASP the Congressional Gold Medal. Nearly a year later, on May 10, 2010, nearly 300 surviving WASPs came to the Capitol in Washington DC to accept the honor from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Congressional leaders. Cornelia Fort Airpark closed in 2011 after flooding damaged most of the field’s facilities in 2010. The land it sat upon was purchased by the Land Trust of Tennessee and Nashville Metro Government and adjoined to the Shelby Park and Bottoms Greenway. The land is presently held fallow as public open space, albeit a marker has been placed on the site by the state government for its historic connection to the first woman military aviation casualty. Aviation continues to be in Fort’s family. Her nephew, Dr. Dudley Fort Jr., is a pilot, and the owner of an Aermacchi SF.260 aerobatic / military trainer. |