| Check-Six.com | |

Offering Aviation History & Adventure First-Hand! | ||

| ||||||||||

The Crash at Sun Valley Mall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The year 1985 was the one of the worst years on record in aviation safety circles. The year kicked off January 1st with the loss of an Eastern Airlines plane with 29 passengers and crew aboard. Then, three weeks later, a Lockheed Electra chartered from Galaxy Airlines crashed near Reno, NV, killing 70 of the 71 aboard. In May of that year, two Soviet aircraft, a airliner and a military transport, collided in flight and killed 94 people. And in June, a terrorist bomb destroyed an Air India 747 off of Ireland, killing all 329 aboard. In fact, on August 12th of 1985, the worst single-airplane accident in aviation history occurred when a Japan Air Lines 747 suffered an explosive decompression while climbing through 23,000 feet. The failure of the rear pressure bulkhead caused a portion of the vertical stabilizer to be blown away, rupturing all four main hydraulic fluid lines. Controlling the aircraft solely by engine thrust, the crew was attempting to return to Tokyo when the aircraft clipped one mountain ridge, flew across a valley, and impacted a second mountain approximately 400 feet from the summit. Of the 524 aboard, 520 perished in the crash. Lastly, on December 12th, a chartered Arrow Air DC-8 crashed just after takeoff off from Gander, Newfoundland, Canada, killing 256 people, 248 of which were soldiers in the 101st Airborne Division. One would hope for a quiet holiday season in the aviation industry. However, on the 23rd of December, only two days before Christmas, tragedy struck again. | ||||||||||||

Jim Graham, 67, founder of General Air Services and a World War II Navy aviator, had flown for nearly 50 years. That day, he had taken his secretary down to San Luis Obispo. Also with him were Jack Lewis, a 48 year-old insurance salesman and financial consultant from Oakland, and Brian Oliver, a 23 year-old student at Diablo Valley College who worked part-time from Graham. Both Lewis and Oliver went along just for the ride. However, the ride would end up costing them their lives. |

| |||||||||||

| Graham’s twin-engine Beechcraft 95-A55 Baron aircraft (N1494G), during approach, was vectored for a landing on Runway 19R. In fact, the same aircraft has been involved in a wheels-up landing only 2 and a half years earlier (with a student pilot at the controls). After being cleared for the approach, Graham was advised that radar service was terminated and told to contact the tower at Buchanan Field. At 8:33 PM, he reported inbound at the final approach fix, and received additional clearance for the approach. About 2 minutes later, he declared a missed approach. He was then instructed by the tower controller to contact Travis Control, but only a “garbled” reply was heard. This would be the last transmission from Beech 94G. After crossing the airport on a South-Southeast heading, Graham’s plane entered a left climbing turn as if to begin the missed approach procedure, then it turned right as if to begin a downward and base leg for Runway 1L. On the ground, witnesses reported the aircraft entered the clouds and shortly thereafter, it reappeared in a steep, descending right turn. | |||||||||||

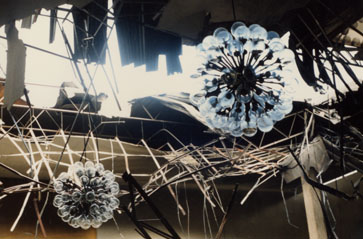

| It then plowed in the roof of the Macy’s Department Store at Sun Valley Mall in a right banking turn, bursting into a ball of fire rising 40 feet into the air, and tearing a 50-foot long hole in the roof. Fiery wreckage scattered across the rooftop, and into the mall below. The three aboard the aircraft were killed instantly. Inside the mall, packed with thousands of last-minute holiday shoppers, it rained upon them broken glass, flaming droplets of aviation fuel, and burning hot metal debris. Blazing roof material caved down upon children and parents, waiting in line to see Santa Claus, scorching many.

| |||||||||||

There was a panic; people running everywhere. The mall began to fill with smoke and soot, and the power quickly cut out. Some thought it was an earthquake, others a terrorist bomb. A paramedic who had served in Vietnam compared the disaster to a napalm bombing. In the firestorm that ensued, shoppers, store employees, and even security guards changed into rescuers, ministering to the injured until additional help arrived. On the ground floor, several burn victims were treated using the water from a decorative fountain in the mall’s courtyard. Winter fashions were torn from their mannequins and changed into stretchers, blankets, and bandages. And clerks from the nearby Sears raided their refrigerators for ice to treat burn sufferers. Nearly every ambulance in the county was dispatched to the shopping mall to expedite victims to neighboring hospitals. The worst afflicted were taken to the Alta Bates Burn Center in Berkeley. In total, 83 people were taken to hospitals and treated for burns, cuts, bruises, and other injuries. |

| |||||||||||

| However, in the early hours of Christmas Eve, the first victim, 22-year-old Pam Stanford, a college student from Antioch who at the mall to simply pick up a wedding ring, was taken off of life-support at enduring burns to over 80% of her body. In the weeks that followed, three others, including a 14-month old baby, would succumb to their burns and wounds. | |||||||||||

The crash polarized the public against proposed airliner service at Buchanan by Pacific Southwest Airlines, which was to have started flights to and from Buchanan to Los Angeles International Airport one month after the date of the crash. The crash also renewed calls for the airport to be shut down (spearheaded by the group People Over Planes), as many felt that the airport was "out-of-place" in the community. |  | |||||||||||

| Four days after the accident, the first lawsuits were filed, primarily at city planners who were considered negligent in allowing a shopping mall to be built so close to an airport (a similar argument as to the crash of a Sabrejet into a Farrell's Ice Cream Parlor in Sacramento, Calif. in 1972). After years of litigation, over 100 claimants (injured persons, as well as damaged and angst-ridden businesses) divided a collected $11.5 million dollars. | |||||||||||

To this day, Sun Valley Mall is still open for business, and general aviation pilots still fly to and from Buchanan Field. All in all, the Sun Valley mall plane crash tragedy brought residents of the East Bay, of all walks of life, together in a common effort to save lives and treat the injured. |  | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Legal Eagles... In legal circles, the crash's investigation had far reaching consequences. The NTSB began an immediate investigation into the cause of the accident, and directed that the aircraft's two engines be shipped to their manufacturer, Teledyne Industries as a costs savings measure. There, the agency planned to conduct a complete teardown analysis, to be conducted by Teledyne engineers working in conjunction with, and under the supervision of, NTSB officials. On learning that the NTSB was shipping the engines to Teledyne for inspection and testing, Graham's widow requested permission to have her technical representative participate in, or at least observe, the teardown inspection, asserting that, because of the related civil litigation, she expressed fears about possible destructive testing and spoliation of evidence. The NTSB and Teledyne refused her demands, and so she sought a restraining order against the NTSB and Teledyne, allegding that the NTSB examination would cause irreparable harm due to the destruction of evidence, deprive her of due process by impairing her legal rights and remedies, and take her property (consisting of these rights) without just compensation. The district court denied a temporary restraining order, holding that the NTSB did not abuse its discretion under applicable statutes and regulations in deciding who shall participate in the accident investigation. In addition, the district court determined that Graham had failed to establish that any constitutional right would be violated by the pending engine examination. Graham immediately appealed, challenging the denial of the temporary restraining order, preventing the teardown until the motion was resolved. On appeal, the court rejected arguments that denying the pilot’s estate access to the NTSB engine teardown resulted in the kind of deprivation of evidence that would constitute a denial of due process with respect to related civil litigation. The court noted that if the appellant’s claim were sustained on constitutional grounds that it would be difficult to exclude others from the investigation, a problem that would be "infinitely multiplied" in a crash involving a major airliner. In other words, an injured person, estate representative, or lawyers representing such parties, is specifically excluded and barred from participation in the investigative process (805 F.2d 1386, 1388 (9th Cir.1986), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 815 , 108 S.Ct. 67, 98 L.Ed.2d 31 (1987)).

| ||||||||||||

We are currently searching for photos of the crash site taken during the investigation. If you have any - please contact us. | ||||||||||||

|